Dwarf Fortress NYC: ASCII Wallpaper, Conceptual Maps and The Landscape Of The Museum

This is the first of hopefully many essays, interviews and articles in a series called "Bridging Worlds", in which LA-based artist and VGT guest author Eron Rauch takes a close look at the blurred line between games and art. These articles are intended as conversation starters about the burgeoning intersection between the fine art world, academic studies of games, virtual photography, and video game creation.

This time, Eron visits Dwarf Fortress at NYC MoMA - where he discovers some of the difficulties in exhibiting games at museums but also accidentally stumbles on some nearby potential solutions.

Iwas in NYC recently, doing all of the typical things that someone who is a tourist-trying-not-to-be-a-tourist does: wandering Chinatown, eating pastrami sandwiches, riding the subway, enjoying the super-late bar closing time and seeing art, all while sweating in the 100 degree heat wave. The thing I wanted most was to spend as much time in air conditioning as possible. I mean, being the professional artist and avid gamer that I am, I wanted to see how the Museum of Modern Art was displaying their new collection of video games. Specifically I wanted to see how they were going to handle Dwarf Fortress, the game that took ten hours of online tutorial videos for me to have even the slightest clue what I was doing.

There have been innumerable discussions about the meaning of MoMA acquiring video games as part of their culturally important holdings. Sometimes thorny theoretical issues like this are best put in perspective by actually experiencing the question physically. In this case, by experiencing the off-white halls where the works are housed; with the smells and sounds of bored teens and tourist parents, turtlenecked intelligentsia, under-slept art students, and museum guards in stuffy suits.

What this means in very practical terms for our lovely Dwarf Fortress is that once you've bought your ticket, downed a $6 espresso in the courtyard (pictured above), wandered two flights of extra wide stairs with the throngs of summer tourists, and made a sharp right, you will be standing in front of the "Design and Architecture" area which currently houses an exhibit called Applied Design.

One important thing to remember about museums is that they have departments, just like colleges or businesses. In this case, Dwarf Fortress, and the rest of the video games owned by MoMA, are actually part of the "Architecture & Design" department. Not all work that an art museum owns is on display at any given point as some pieces go on loan to other museums while most others sit in climate controlled storage until they are needed for a show. In the case of Dwarf Fortress, it has been brought out to public display twice since its acquisition. Once for a show called Talk to Me: Design and Communication between People and Objects in 2011 and more recently in this show, Applied Design, which is on display until January 31, 2014.

Dwarf Fortress, and the rest of the video games owned by MoMA, are actually part of the "Architecture & Design" department.

To give a sample of the other departments in the museum organization, most of Jackson Pollock's and Jeff Koons's works are in the "Painting and Sculpture" division; but their drawings are in the "Drawings" department. "Photography" also has its own curators and shows, as does "Film." MoMA has two additional divisions that are designed to catch the rest of heterogeneous types of art not included in the other divisions, "Prints and Illustrated Books" which could house both comics and Picasso etchings; and then there is the strange union that is the department of "Media And Performance Art," which is seemingly a catch-all for anything that doesn't fit anywhere else. "Architecture and Design" is another such a hybrid division, holding pieces as diverse as chairs, lights, architectural plans, toys and even an Army Jeep.

Part of why I want to talk about these potentially boring institutional topics is that the departmental categories have real repercussions in terms of the way the landscape of the museum gets constructed. The museum's floor space is carefully divided amongst these various departments and special exhibits.

The Applied Design show takes up two of the three "Architecture and Design" gallery spaces. These adjoining rooms are filled with pert post-modernist furniture on risers, the walls hung with swanky graphics, pristine shelves sit against the walls and are adorned with tastefully placed gizmos and gadgets, all while architectural models sit stoically on pedestals. Walking forward through the show, you hit a small back hallway that divides the two equally eclectic halves of the show. This interstitial hallway, on the other hand, has nothing on the floor and nothing on the wall but a couple of screens with curious glowing text placards next to them. If you examine the area closer, there are a couple of built-in buttons and joysticks are visible set in the wall. There is a windowed dead-end on one side pouring light in to what otherwise might be mistaken as a place to wait for an elevator.

Oh wait, those are a pair of elevators opposite of the small screens.

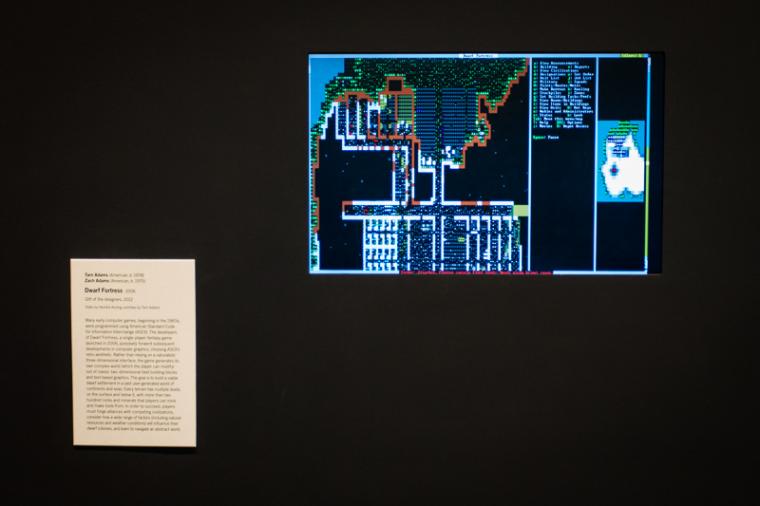

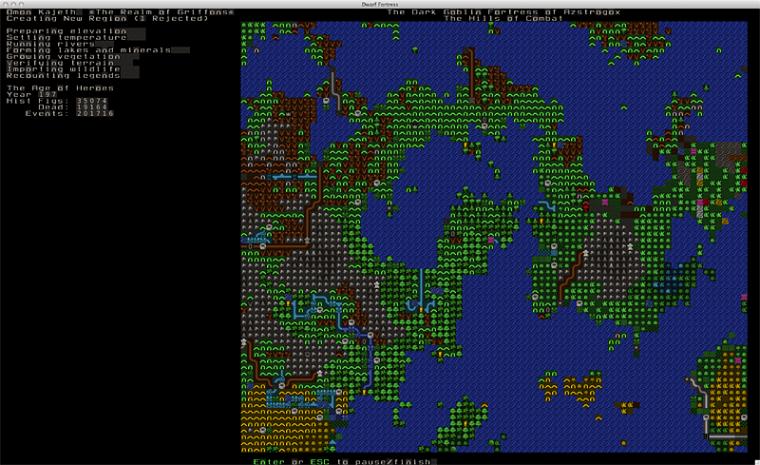

The screens on the wall there house a number of classic arcade games like Donkey Kong, more modern games like Katamari Damacy, as well as the indie classic Passage, all of which have controls to play. In the midst of these games is Dwarf Fortress, with a demo looping quickly by on a smallish screen, somewhat ironically glowing wall text situated below and to the left:

Read wall text? Y/N

Y

"Many early computer games, beginning in the 1960s, were programmed using American Standard Code for Information Interchange (ASCII). The developers of Dwarf Fortress, a single-player fantasy game launched in 2006, purposely forwent subsequent developments in computer graphics, choosing ASCII’s retro aesthetic. …."

Iwas immediately struck by the fact that initially it seemed like the curators were basically treating Dwarf Fortress like a retro screen saver, like a visual tchotchke with no context and no way to interact with the game. If you want to know even the most basic idea of why anything on the screen is happening, say why that green "S" is moving, you would have to dig out a smart phone and do some heavy duty Google-ing to realize that's a snake. That is, while the wind-powered de-miner by Massoud Hassani (a near prerequisite piece for any design show) is instantly legible about what it so ingeniously does, the exhibit mode for Dwarf Fortress gives the viewer no way to understand the raw horsepower and intricacy of the algorithm that is the heart, the insidious art, and the design genius of the game.

In fact, seeing the display, I was a bit flummoxed that I had learned so much more about the game from the text of a New York Times Magazine article than actually seeing the object in one of the most preeminent museums in the world. In fact, the truly stunning thing about Dwarf Fortress is how the game makes you painfully aware of the stupendous number of challenges and choices that we take for granted. We live in a world with nested landscapes: some visual, some institutional, and the game is not just an ASCII screen saver, it is a meditation on how overwhelmingly complex it is to even make a crude dwarf chair, let alone the low-slung museum-pieces sitting in the next room over.

At this point I was more confused by my experience at MoMA's video game display than anything else.

But in the museum the game is reduced to a pre-programed loop where the infinitely branching complexity is left mute, illegible, un-explorable, and most critically, immutable. For anyone that has played Dwarf Fortress, these attributes are completely antithetical to the overwhelming messy experience of interacting with that unholy beast of an algorithm that has consumed a decade of its two creators' lives and according to the New York Times Magazine article is, "on the same scale as modern engineering software for designing aerospace hardware." Yes, some purists play the game with only the original ASCII set, but most players use a shifting assortment of third-party tile sets, external mods, wikis and interface hacks to manage their multidimensional interface with this nigh-eldrich algorithm.

At this point I was more confused by my experience at MoMA's video game display than anything else. With the limited resources I was given to examine the game in the Applied Design show, I could only generally follow what was actually happening on the screen - and I can reliably get a fortress up and running! I could hardly imagine what most viewers, many of whom might only have a passing experience with video games via their phone, were taking away from the display.

Drifting absently while I was thinking about the problems with showing such a complex system in a museum, I walked out through the second gallery of curious furniture and space-age architectural models, and wandered into the the Paul J. Sachs Drawing Galleries, which occupy the adjacent spaces on the third floor of MoMA. The show in this gallery was called A Trip from Here to There, which featured pieces of conceptual-leaning art that dealt with geography and mapping. Specifically, the works in the show were a series of moderate scale pieces that explored the ways that our cultural and institutional structures (like maps) are just one of many ways to experience the world.

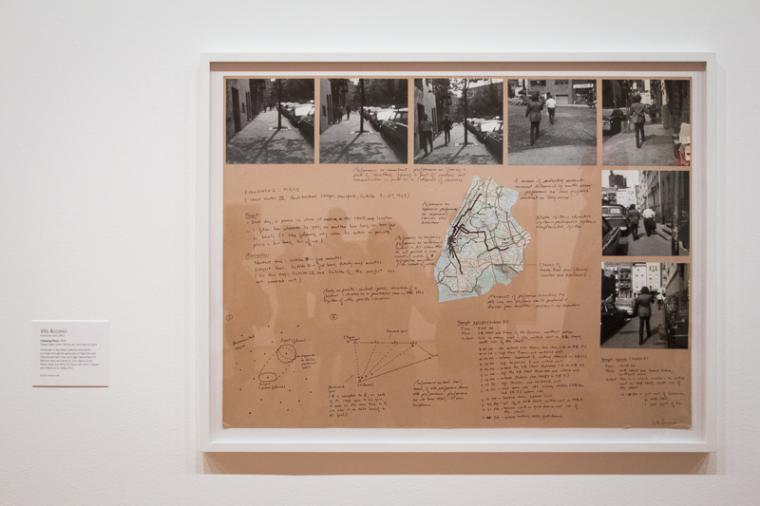

One of the pieces in the show was the classic Vito Acconci Following Piece. As a way to explore the multivalent geography of large cities, he randomly chose people on the NYC street and followed them for as long as possible, mapping and photographing these explorations:

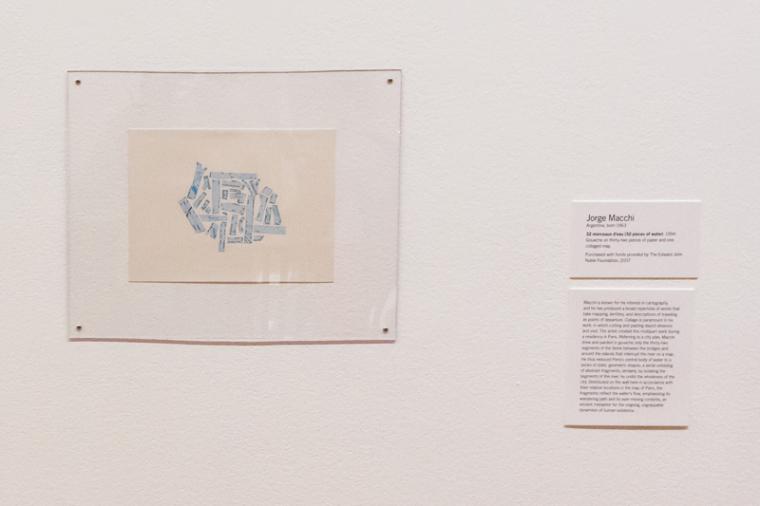

A piece by Jorge Macchi called 32 Morxeaux d'eau was a series of 32 small drawings of the abstracted shapes made by the river Seine as it was cut in to pieces by the bridges of Paris, creating a new and novel way to explore the abstraction inherent in maps. Pictured is the overview of all the maps source parts jumbled together:

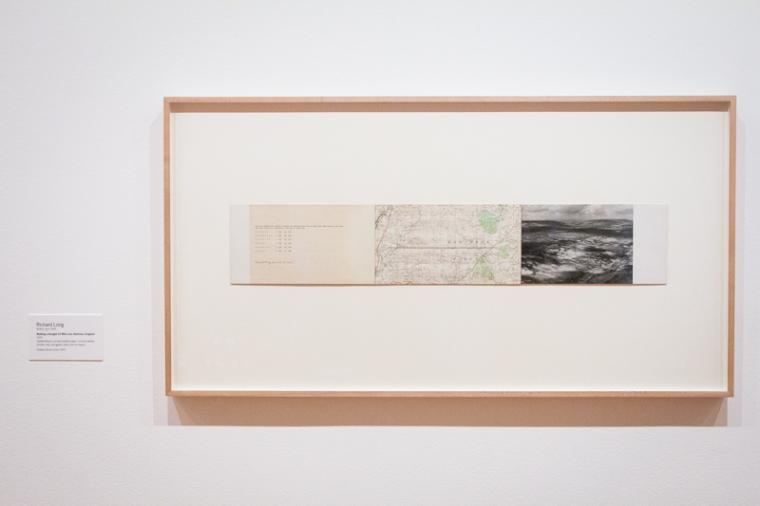

Richard Long was represented by his piece Walking a Straight 10-Mile Line, Dartmoor, England, in which he does exactly what the title suggests, tries to walk across a landscape in a geometrically straight line:

At this point in my visit to MoMA, I was starting to get excited by a pair of ideas that occurred to me. First off, while the use of ASCII to display such large amounts of data is novel in a retro-sort of way, Dwarf Fortress is much more a spiritual kin to the fragmented, slightly surreal, re-imaginings of landscape in A Trip From Here To There (which even sounds suspiciously close to Tolkien's subtitle for The Hobbit, "There and Back Again") than it is to a chair or static architectural model for a house that will be built.

Museum departments which display video games have much to learn from their contemporary art brethren.

Second, and perhaps more importantly, is a small but critical observation about the three works I mentioned in the "Drawing" galleries: They display information in multiple ways. If you look at the photographs above, each piece uses a complex multi-part, combination of maps, drawings, symbol keys, photographs, text, and gallery displays to communicate their larger point and help the viewer to understand what the underlying project is trying to do.

Based on my experience at MoMA it feels as though it would behoove museum departments which display video games to learn from their contemporary art brethren and adopt some of these strategies for showing viewers these malleable, idiosyncratic worlds.

For example, I would love to have seen 32 different printouts of randomly generated worlds or "completed" fortresses on the nigh-barren walls in that hallway where Dwarf Fortress was looping. Having a big, glossy poster that is a key to all of the ASCII in the game would have been a fantastic way to reinforce what the wall text was highlighting. Annotated notes or source code from the creators would be interesting. They could even run some of the better tutorial videos (such as VoV's "Plays" series). Even including strategy guides or game manuals for the viewers would help. (In an Applied Design context, why not include the physical hardware of some of the classic arcade machines or even Nintendo peripheral devices like the Zapper?)

If museums were to become more ambitious, which they surely will with the purchase of such games as EVE Online, I would propose that it is time to create a museum position that is the virtual or code equivalent of exhibit designers and preparers. That is, just like the physical museum builds walls, paints background colors, puts up wall text, and hands out pamphlets to make exploring the works in the museum more legible, these virtual preparers would be in charge of creating mods and interfaces to allow non-initiates to experience important parts of games.

For instance, I would have loved a mod that just lets me, a museum goer, to go through the "Legends" mode (history) of a series of random Dwarf Fortress worlds. How about a mod that let me hit a single button and watch a world generate in real time in the gallery? What about a mod that gives me access to the "k" (examine) command and the four arrow keys to explore the world while locking out everything else, much like the observer modes in eSports games like StarCraft 2?

I hope to start a conversation about novel but more useful ways to let visitors to the museum see why these video game art objects are worth studying.

In this essay, I wanted to contextualize the experience of one of the first museums to start collecting and displaying video games and suggest some possible ways to enrich the experience. I've assuredly been a bit glib, and to MoMA's credit, the online gallery of works in the Applied Design show is frankly more coherent than the show itself. Yet, by highlighting some of the strategies that are being used next door in the same institution, I hope to start a conversation about novel but more useful ways to let visitors to the museum see why these video game art-objects are fascinating and worth studying without making every patron learn the intricacies of how to play such an overwhelming game.

Since the ever-expanding realm of video games will invariably be an increasing part of the art and museum conversation, it seems critical to the future of both museums and galleries to connect these new acquisitions into the broader, pan-departmental, pan-art-historical conversations and methods of the world of art and design.

Until then, I'll just remember standing in MoMA, confused about how this incredibly idiosyncratic and complex game was being shown, but briefly recalling that my poor dwarves at home are starving because of a few tiny bad decisions in the earliest stages of planning for their foray into the wilderness.

Eron Rauch is a Los Angeles based artist who works with photography, books, essays, drawings, and installations to explore the relevance and interconnection of the shadowy regions that linger just at the ever-shifting borders of the traditional fine art world and the American media landscape. From anime conventions, to apartment architecture; from renaissance faires to video game landscapes; from vernacular photography to origami; from Harajuku fashion to fantasy novels; his work explores the ways that latent desires build deeply idiosyncratic, often lonely, personal geographies. He received his MFA from the California Institute of the Arts in 2006 and has been involved with the Creative Underground Los Angeles collective since December 2012. More of his projects can be found at

http://eronrauch.com and

http://creativeundergroundla.squarespace.com/.