Echoing Histories: Impressionism, Indie Games and Artistic Revolutions

"Bridging Worlds" is a series by LA-based artist and VGT guest author Eron Rauch about the blurred line between games and art. These articles are intended as conversation starters about the burgeoning intersection between the fine art world, academic studies of games, virtual photography, and video game creation.

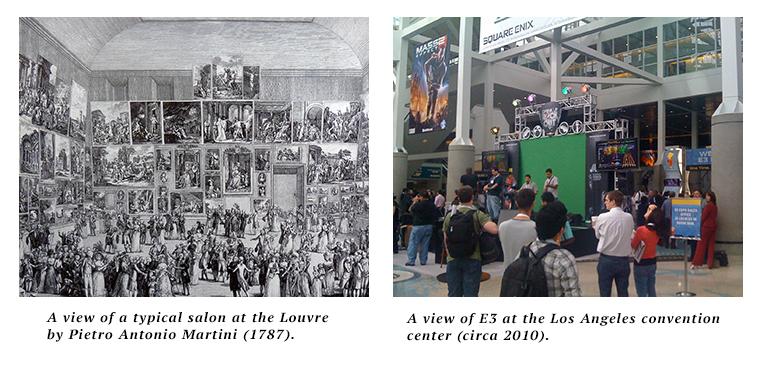

Imagine the scene: Paris 1874. The city is still in turmoil from the massive fallout of the Industrial Revolution. There are wild all-night cabarets, horse races to bet on, and salons where drinks and culture are passionately discussed. A great obsession with all things Japanese is the fashion amongst the newly well-off as the world continues to grow smaller. You’re at a party, sipping champagne, talking about the most important art event in the Western world at the time, the Salon du Paris.

Cut to Los Angeles, 2013. The city is still in turmoil and perpetual change after the fallout from globalization vis a vis the banking crisis and tech bubbles. The electronic dance music scene is exploding. Ultimate Fighting Championship title cards are the talk of the town, and hipster bars and neo-speakeasies fill the alleys. A great obsession with all things Japanese is the fashion amongst pretty much everyone. I am at a party, sipping a micro-brew beer, talking about the most important video game event in the world at the time, the Electronic Entertainment Expo.

But the really juicy conversation, the topic that everyone brings up, isn’t who won nor who got the best press, but, my, my, those upstarts! At the party are a number of very successful people - folks who are the toast of those important events - chatting: “They didn’t even have a jury, that means anyone can have their work seen! How will anyone know what is good?” one man says sloshing his drink slightly in the night air. “Yes, their work is so modest in scale. It’s hardly worth paying attention to.” Gruff nods mingle with the smoke of expensive cigars. “I mean, their subject matter is so banal. They don’t seem to have any grasp of the grand themes of myth and history that tie us all together!” “Yes, they just depict everyday life. People won’t pay money for that!” Each looks to the other, somewhat uneasily, as though they are trying to sniff out a traitor. “Yes, I could respect them more, but it looks so bad, so unfinished - almost like sketches - nothing more than impressions!”

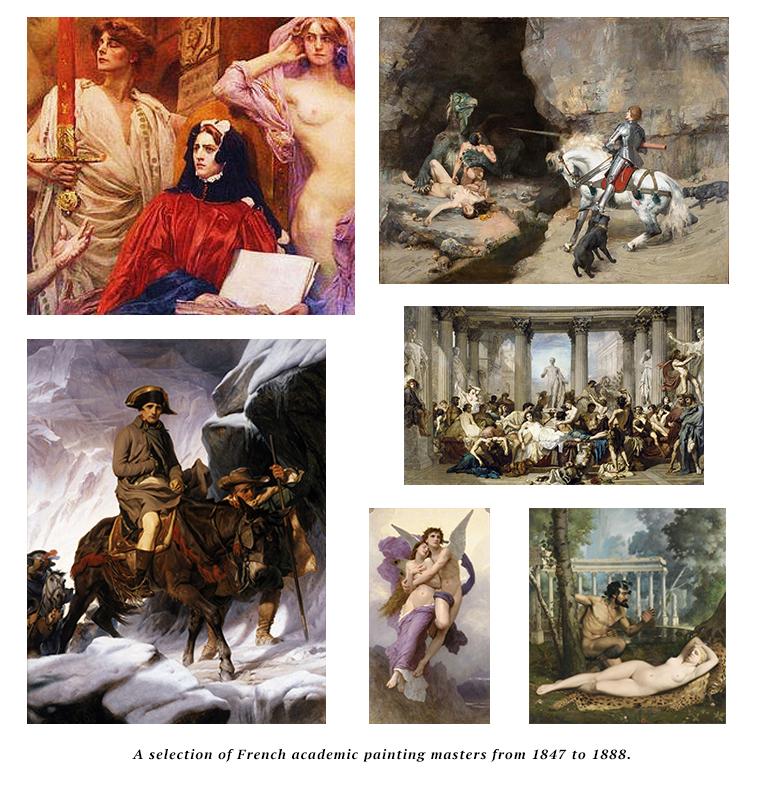

You see, most people would like to think that if they were alive in Paris in 1874, they would have been cheering on the Impressionists’ effervescent break with tradition, been one of their champions, and slugged down wine in the courtyard bars as they argued the finer points of their work. But that is a fantasy. Most of us would have been just like everyone else in Paris and lined up to go see the grand history paintings and voluptuously rendered Venuses in the massively anticipated yearly art show at the Louvre that was held by the Académie des beaux-arts.

Let's consider the social and artistic overlaps of the rise of 19th c. Impressionism with the current growing prominence of “indie” games.

Unless you’re a specialist in art history, you’ve probably only ever heard of the Académie des beaux-arts [which I will refer to as the Academy for simplicity’s sake] and their Salon du Paris in a very tangental way. That is, because they were the institution with which the Impressionists broke from to pursue their own vision of painting the modern world. But over the course of the previous 200 years, the Academy and their juried salon was one of the, if not the, most important group that defined the criteria for a good painting for most of Europe. The school itself was similar to a trade school set up to formalize the group of well-to-do artists (and their handpicked successors who slaved away under long hours for decades as assistants before creating finished work themselves) who produced the grand gilt-framed art which filled the homes of the nobility and entertainment spaces favored by the newly rich.

You may think I am rambling off into the finer points of an art historical period a century past its prime. Indeed, today Impressionism is so tame that your parents probably have a cheap reproduction of a Monet waterlily or Degas dancer sitting above their toilette. But in its historical context Impressionism was radical and the circumstances surrounding its rise have some fascinating social and artistic overlaps with the current tensions rising in the gaming community with the growing prominence of “indie” games. (See **Footnote for some caveats about that term!)

To emphasize my point, I should note that while synthesized from a couple different sources to make it more concise, that imaginary party conversation is drawn from criticisms of the first Impressionist independent show in 1874 as well as a party I happened to be at in the Fall of 2013 with a bunch of my friends who work for large video game publishers talking about the rise of indie games.

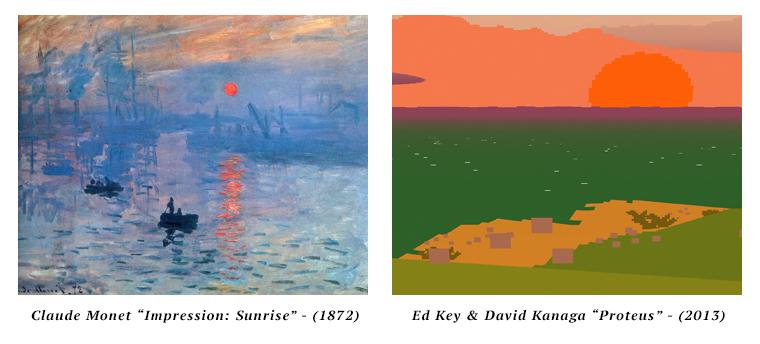

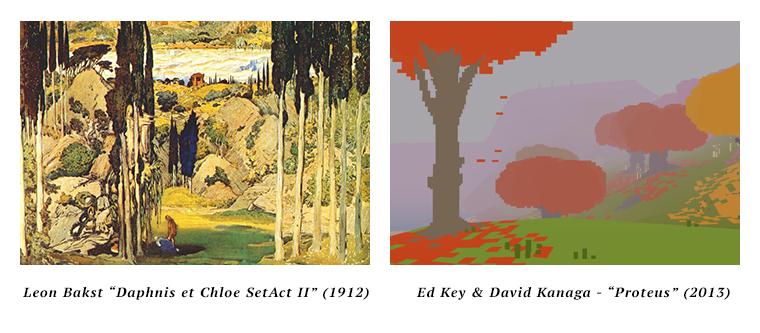

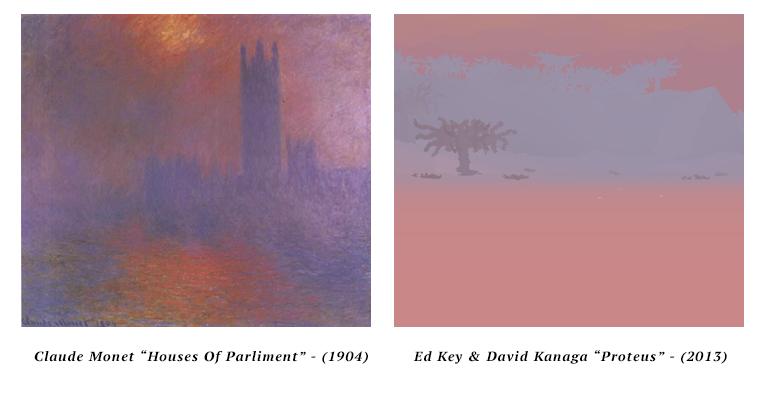

The game that got me thinking most about the overlap of these two historical moments of artistic change was Proteus. It was also one of the primary games under discussion at the 2013 party along with Braid, Starbound, Gone Home, Dwarf Fortress, and such. The accusations that Proteus was pointless, brashly colored, not technically realized, and basically “unfinished” immediately triggered long-buried memories of undergraduate art history classes. Specifically, I had flash backs to an impassioned teacher reciting all the criticism that was leveled against the impressionists from the more conservative-leaning newspaper reviewers (which are fascinating to read). Partially why Proteus became my pivot for thinking about artistic change was that buried in the credits of the game is a brief mention that some of the music used in the game is quoted from Ravel’s “Daphis et Chloe”, an orchestral score to a ballet held up as one of the greatest masterpieces of impressionist music.

To continue my meander through the gardens of history, I would like to ponder the experience of Emile Zola. He was a writer and also the first critic to publicly see Impressionism in a positive light. His process of acceptance was hardly instantaneous. He was a radical proponent of “realism” in fiction. In that light, his defense of impressionism might seem odd, given that they broke most of the rules how to make a painting realistic. But the more he engaged with them the more he realized that once you could let go of the traditional rules by which paintings were judged, the Impressionist paintings were actually a more direct and vibrant expression of what modern life really felt like. In fact, the whole label “impressionism” was originally an insult that was leveled from another critic that stuck. Zola was simultaneously publicly writing about how he viewed the Impressionist works as deeply realist, both in the way they described modern life but also, critically, in the way they directly engaged with their status as paintings.

Why is an argument between painters and art critics in long-ago Paris valuable to discuss in regards to video games now?

But why, you might ask, is an argument between painters and art critics in long-ago Paris valuable to discuss in regards to video games now? While there are, of course, wildly different concerns between the mediums, let me draw these two worlds closer together by looking at the criteria that was used in the Academy and the Paris Salon. First off, they had a formal ranking of painting genres. These rankings of importance were decided on by the people in charge of school and the Salon, who were also deeply concerned about what kinds of paintings sold well to their prime market (owners of massive villas). Foremost was History painting, called “the grand genre”. This was a category that included historical scenes of politics and wars alongside Greek and Roman mythological and other “large” allegorical/religious scenes. Next was Genre painting, which were elevated scenes of contemporary noble life, such as the famous Gerome painting, “Duel After The Masked Ball” (which I had on my wall in high school, and still quite like, returning to it 15 years later). Then came Portraiture, typically of nobles and generals, present and past. Then came the genre of Still-life. The rear was brought up by the lowliest of genres, Landscape.

In the Academy, scale and scope were also a way to quickly judge the value of a painting. Large paintings with many intricate elements were inherently considered more important than smaller work. Photorealistic rendering with the smoothest blending of tones was prized, but the people in the paintings had to be deeply idealized: The men handsome, rugged and muscled; the women seductive, pale and voluptuous. Linear perspective was considered a prized technical point, with extra weight being given to realistic use of atmospheric effects. Also critical was a slickness of surface. In fact one of the most scandalous features of the Impressionist paintings that partially led to the accusations of being unfinished was that they refused to use the traditional gloss varnish which the Academy painters applied to the surface of their canvases to hide their brush strokes and to suffuse the whole thing with a warm glow. Like the myth of Zeuxis, who supposedly painted grapes so realistic that birds would try to eat them, the goal of a great Academy painting was to have the audience forget they were even looking at a painting. It’s important to note that no women were allowed in the Academy and most of the paintings were assumed to be sold to men.

What other academy seems to values mythic retellings (especially sanitized Euro-centric versions espoused by Joseph Campbell) and war most highly as subject matter? What group of artists values massive scale and scope (and budgets) most highly?

What other group tends toward using conventional settings and stories and favors sequels and remakes? What other group places the highest value on ever-increasingly photorealistic rendering of ultra-idealized human forms?

What other people have a massive interest in pushing the edge on smoke and light effects in three dimensional spaces? What other group of producers strive to hide the made-ness of the object behind shine, polish, slickness, lens-flare and even literally has options you can check in the menu to turn on “full screen glow”? Who else holds suspension of disbelief and immersiveness as their highest goals?

Come to think of it, this group also seems to have some difficulty including women in its thinking.

From our vantage point, it is probably hard to see Impressionism as anything as near as scandalously radical as it was viewed in its era. But if you set aside modern preconceptions and look at the values of the Impressionist painters you can begin to reconstruct why they so confounded the Academy. First, Impressionism, at its radical core, proposed that there shouldn’t be any artistic gatekeepers, commercially or artistically. After all, part of the revelation that defines thinking in the modern era is that humans perceive the world in deeply subjective way (the modern era also brought forward the rise of psychology) so every artist should make work from their point of view.

To this end, even though this part is often left out of the textbook descriptions, the Impressionists didn’t even wholly discount the current style of Academy painting. The initial Impressionist independent salon had a large percentage of traditional paintings that would have been at home in the academy, and some painters like Manet and Cezanne continued to submit their work to the Salon jury. But overall the Impressionists were attempting to move the realm of art out of the tight grasp of old men and the nobility toward a new focus on the middle classes. Women were also welcome to exhibit alongside men as equals (though they were not represented in equal numbers by any stretch, a problem that persists in art institutions to this day).

Another concept that the Impressionists promoted was that content should be keenly observed from daily contemporary life, which included domestic scenes, the crowds of the theatre, drunks, trains, horse races, urban landscapes and the like. Additionally, they proposed that paintings were first and foremost paint and that attempting to treat them as neutral “windows” was not only silly, but limited the kinds of ways that the medium could be used to its maximum potential expressiveness. A corollary was that compositional and scale rules were anything but neutral, which was partially why the Impressionists so adored the bold compositions and modest scale of Japanese wood block prints as living proof that art forms could evolve with other sets of rules than the Academy. In these ways, the independent movements brewing in Paris were rooted in the importance of expanding the vocabulary of painting. Much the same way that early cinema came alive once producers realized that it was different than sitting in a chair in live theater; that you could move the camera, zoom, make things out of focus, and even make cuts, which could make the experience more intensely visceral even though it wasn’t realistic when put in the terms of the established theater paradigms!

These two systems of the Academy and the Impressionists generated two very different sets of artistic (and cultural) values. Artistic values are not inherent or innate - they are instead driven by cultural, institutional, economic and historical forces. One clear example of the interrelatedness of the formal and cultural forces might be best exemplified by the Academic viewpoint that women can’t be artists which was derived from centuries of religious and cultural weight. The Impressionists, who decided to break with the past and look with direct eyes at the newly modern world, realized that the old ways of thinking about women artists were outmoded (even if many of them, like Gauguin, continued to be chauvinist jerks). As you can see with the interest in intimate domestic scenes, middle-class gatherings and public spaces, new ways of weighing value led to new types of stories being told.

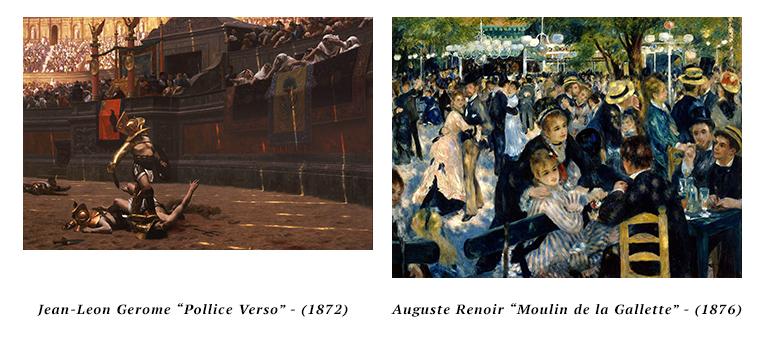

By eschewing the supposedly “grand” and “universal” subjects and the ultra-clean rendering of the academy in favor of a deep interest in the intimate, fleeting and contemporary moments of life, the Impressionist painters sparked a revolution by foregrounding what it must have felt like to be in Paris in 1874 with the air filled with plumes of steam and haze. Photography was newly invented, and in 1873 the development of halftone screening allowed its mass reproduction all while the world was being connected with more communications technologies like the telegraph. The middle class entertainment scene was quickly growing, with the infamous Moulin Rouge but a handful of years off. To showcase how these differing criteria for “good” painting resulted in very different stories, not just aesthetics, in a more visual way examine these two paintings below. They were both made within four years of each other during beginning of the modern age in Paris:

For me, the real lesson that can be mined out of these similarities is that often new movements in an art are disconcerting because they break down our simple ways to determine what is and isn’t good, and as recent research into music taste has shown, human psychology does not like taking risks, especially with art that might put them at odds with their society. Specifically, the introduction of directly observed, non-idealized subject matter from contemporary and banal daily life was a major shock to the system of painting that was obsessed with a pre-defined set of highly idealized and grandiose moments. But the shock also came with an opening of scope. Painting now had a broader realm thought that it could explore, including the fullness of itself.

Human psychology does not like taking risks, especially with art that might put them at odds with their society.

From our vantage point it’s so easy to have false daydreams that everyone in Paris in 1874, was hip to the radicals, riding ahead of the great wave of history on a canvas of pastel picnics and wild blue night scenes. But Paris from that period is rendered by the rules of the winner’s history, the formerly grand Salon long forgotten. How easy it is to overlook how much sway social conventions, institutional inertia, and making money have over what art we choose to (or are allowed to) engage with and the criteria with which we deploy to judge them.

It was merely a happy accident that these two conversations – one about Impressionism, the other about the rise of indie games - echoed across a century but hopefully their paring can become a way for all sides to contextualize the deeply human conversation in which the video game world finds itself enmeshed in right now. By gaining some context perhaps it can become clear that the idiosyncratic works of art, even if their methods and vocabularies seem strange or disconcerting initially, are actually often strategies to find a new vocabulary of techniques and forms to speak about these anxious, messy, slippery moments of change that we are going through globally in 2014.

Read the rest of Eron Rauch's articles here; all of VGT's English features can be found here. See below for footnotes.

**FOOTNOTE: To digress slightly, I do want point out that I fully understand the fraught nature of the word “indie” here. In fact, being a music and movie fan before I was a fan of video games, I find the video game world’s hand-wringing about the validity of this term amusing. For context, given the recent swirl of dialog about co-option and cooperation of indie game “style” and the recent influx of large amounts of money, we’re about a decade after the movie industry went through similar upheaval via the Sundance festival effectively becoming a recruiting fair for the major studios. Additionally, we’re at least two decades after the underground music scene laughed the word indie (along with the even more silly term, “alternative”) right out of the room of usefulness/tastefulness as the term was seemingly used to describe any rock band during the ‘90s. Nevertheless, I’ll continue to use the term in this essay with all these reservations acknowledged, because it is still the primary word used in the North American vernacular to denote that broad swath of markets and creators, from twine games to big-budget retro, from Proteus to Journey, which isn’t interested in the same aesthetics as the AAA market, regardless of affiliation or funding.

In fact, to let this footnote get even more labyrinthine, even impressionism was quickly co-opted over the next couple decades once the Academy realized there was solid money and prestige to be garnered in a newly popular, formerly avant guard, style. Many of the great modernist movements that came later were as highly critical of the rote values of late-impressionism as the Impressionists were of the late-Academy. During the 1960’s, in a backlash against the often egomaniacal tendencies of abstract expressionism, a variant of the highly-controlled, hyper-technical photorealistic rendering came back in to style with artists like Chuck Close. Which is interesting because Gerome, the star of the Academy, actually loved photography, a medium which wouldn’t be respected as art for many decades after his death. To end this ironic meandering through the messy underbelly of my argument, there is a move in art history to give more credit to the almost forgotten academy painters of the 1800s precisely because the modernist and post-modernist movements have been so successful in promoting a view of the world that is predicated on multiplicity of value systems!

Academic Paintings, Clockwise From Upper Right: Gustav Srand “St George and the Monster” (1888), Thomas Couture “Los Romanos de la Decadencia” (1847), Adolphe-Alexandre Lesrel “Pan and Venus” (1865), William Bourguereau “Le Ravissement de Psyche” (1895), Paul Delaroche “Napoleon Crossing the Alps” (1850), Jean-Paul Laurens “Untitled [Detail]” (Unknown, Likely Late 1800s)

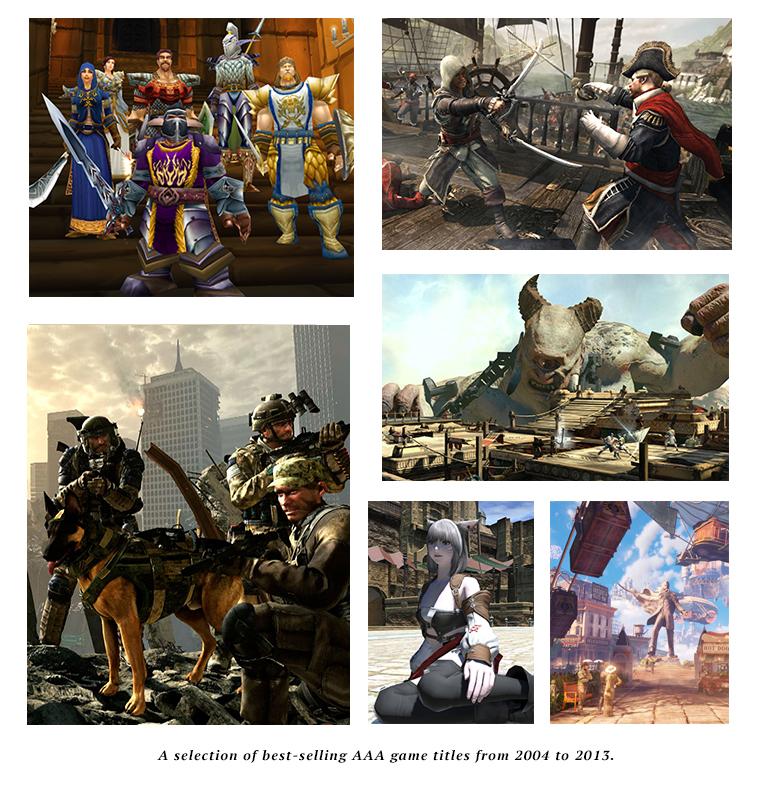

AAA Games, Clockwise From Upper Right: Ubisoft, Assassins Creed IV: Black Flag (2013), Blizzard Entertainment, World Of Warcraft (2006-Present), Sony Computer Entertainment, God Of War: Ascension (2013), Irrational Games / 2K Games, BioShock Infinite (2013), Square Enix, Final Fantasy XIV: A Realm Reborn (2013), Infinity Ward / Activision, Call Of Duty: Ghosts (2013)

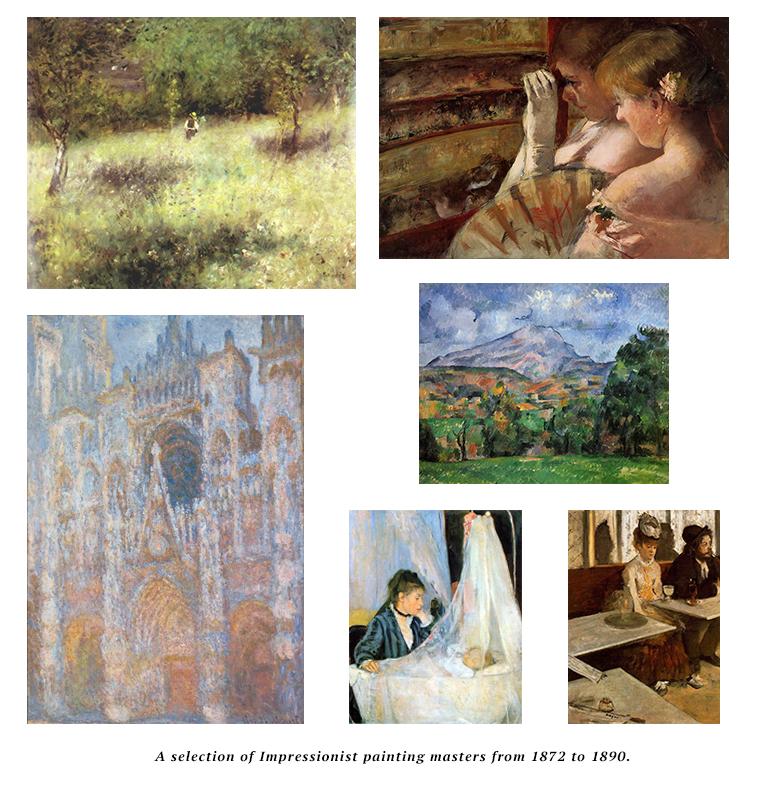

Impressionist Paintings, Clockwise From Upper Right: Mary Cassatt “In The Box” (1879), Paul Cézanne “Montagne Sainte-Victoire” (1888-1890), Edgar Degas “Buveurs d'absinthe (Absinthe-Drinkers)” (1876), Berthe Morisot “Le Berceau (The_Cradle)” (1872), Claude Monet “Rouen Cathedral, the portal. Morning Sun, Blue Harmony” (1893), Pierre-Auguste Renoir ”Spring At Chatou” (circa 1872-1875)

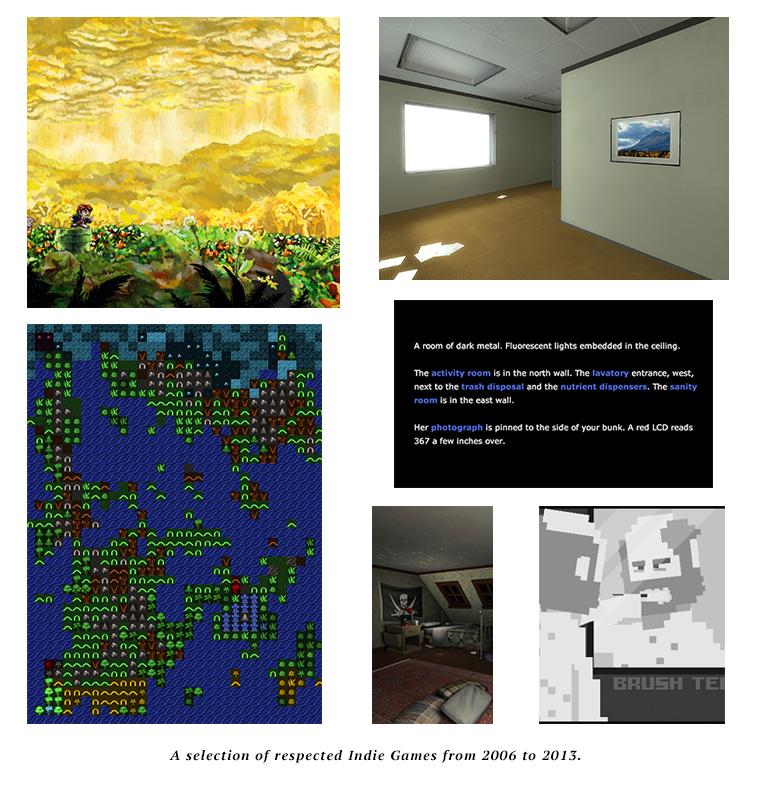

Indie Games, Clockwise From Upper Right: Davey Wrenden / Galactic Cafe, Stanley Parable (2011 and 2013), Porpentine, Howling Dogs (2012), Richard Hofmeier, Cart Life (2011), Steve Gaynor / The Fullbright Company, Gone Home (2013), Tarn & Zach Adams, Dwarf Fortress (2006-Present), Jonathan Blow / Number None, Inc., Braid (2008)