Demystifying MOBAs: Characters - Representing A Digital Pantheon

The relationship of characters to narrative is also fundamentally vastly different between the games, and tends to indicate many larger design intentions. In DotA2, the characters names are abstracted into archetypal names in a manner similar to chess pieces or tarot cards, such as “the Bishop” or “the Fool”. In DotA2, champions are mostly named generically such as “Dragon Knight,” a knight who can turn into a dragon, or “Invoker,” a mage who casts a wide variety of spells. Given its history as a fan-made modification of another game, it is important to note that it also has few non-sequitur name references to anime such as “Lina the Slayer”. In this way, DotA2 constantly re-emphasizes its focus on systems, strategy, and rational analysis, on its status as a game, over any form overt narrative passion.

When it comes to LoL all of the characters exist as specific properly-named characters such as Jarvan IV and Irealia that exist in a coherent world that is in the midst of a war between two empires similar to Boromir and Saruman in Lord of the Rings. But the specific narrative material is often such offhanded genre filler that even the casters (paid by Riot) will openly mock its insipidness during official event broadcasts. In a strange predictive twist of fate, the internet slang term for this sort of nonsense backstory has from a time long before LoL been nicknamed “lolore.” But giving all of the characters specific names, stories, and personalities takes a great deal of time (and hence money), so why would Riot, who made their game as a clone of DotA2, do all this this extra work?

The answer might be found in LoL’s curious market position which is atypical in the video game industry: people who play it often mostly play this single game and the company who makes it only has this one game on the market. Anything that makes the world richer or makes players more likely to invest time and money is clearly beneficial to its monovalent economic model, and perhaps the easiest way to do this is to systematically entice emotional investment in the characters. That is, merely by changing the character name from the generic “Dragon Knight” to the proper name “Shyvanna” and giving her a story, as a persecuted half-breed seeking revenge on her father’s murderer, the game feels richer (or stickier as investors might term it).

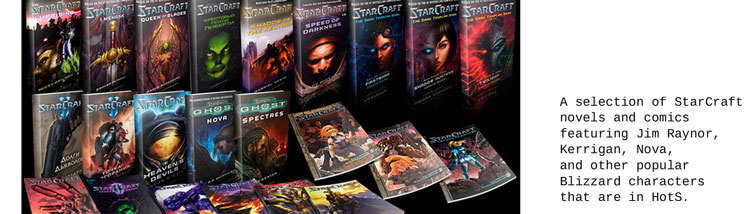

By contrast in HotS, there is no unifying narrative for the game itself. It is just a giant multi-dimensional brawl between all the proprietary characters from Blizzard’s other games. That means that, like in Nintendo’s hit Super Smash Brothers, the characters are all beloved by fans for their long-running stories in their respective games. The characters in HotS are mainly core playable characters in other franchises, or their equally famous villains. You can choose to play the hero of the StarCraft 2 series, Jim Raynor, whose lengthy wiki mentions GameSpot’s community voted him one of the top ten heroes in video gaming, or as Ilidan Stormrage, the villain from the World of Warcraft: Burning Crusade storyline, famous across the internet for his line, “You are not prepared,” which is used in an untold number of memes.

These characters have often had numerous novels published about their exploits, as well as a bevy of toys, comics, cosplay, and loads of fan art and fan fiction made about them. This is big part of the appeal of the game, both for fans and for Blizzard’s investors. Old school players get to take control of a favorite character that they have grown up with while new players can discover (and of course buy) the other Blizzard games through an introduction to their main characters in HotS.

Art History Is For Noobs

Alongside the character names and stories, one aspect of picking a character that is noticeable even before you play a game is the art style. The style of art doesn’t get much conscious attention, buried as it is amongst the overwhelming practical choices given to new players, but the house art style of each game holds a wealth of interesting indications about how the games wish to present themselves.

DotA2 is based on the game Warcraft 3, but has moved toward a more classic fantasy style with a focus on organic textures and stylized but still (vaguely) realistic proportions rooted in the tradition of 70s and 80s Lord Of The Rings or Dungeons & Dragons oil paintings. Valve even created a whole new engine for the launch of DotA2 just to handle natural fabric effects.

LoL is curious because it started as a clone of DotA which initially featured rather middling classic comic-book style art and then evolved toward using highly wrought illustrations very rooted in late 90s-to-current mainstream cover illustrations from Marvel, DC, and Image with extreme physiques (think 20-pack abs and giant balloon boobs), use of forced perspective, and blindingly shiny dramatic lighting across a slew of neon colors.

Riot is currently in the midst of a massive overhaul of its LoL art. They are trying to remove most of the remnant assets from their early years, often replacing them with assets created for the newer Korean and Chinese versions of the game, which has a nod toward anime and manga. The old art character style is maybe best represented by the notorious Snow Bunny Nidalee, and the new style is certainly represented by Nightblade Irelia or Neon Vi.

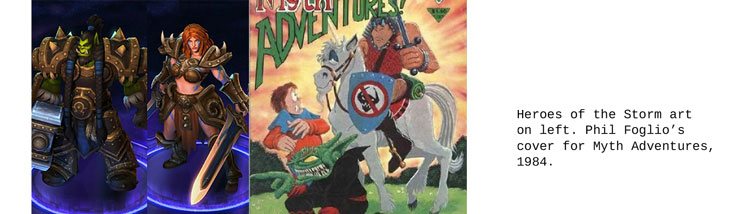

HotS continues the Blizzard house style which is rooted in 70’s fantasy-comedy illustration, itself a product of the head shop culture and underground “comix”, with highly cartoonish, thick bodies. There are bell bottom pants galore, barrel-chested men, curvy women, and oversized shoulder armor, and fists that often literally look like hams when formed with polygons.

The Moneychanger Lurking In The Shadows

While picking your first character, the differing economic models of the games are immediately highlighted. In DotA2 you immediately have full access to every character in the game at their full power. Though egalitarian, this makes for a daunting decision for new players, given that there are 110 different options! Throwing new players into the deep end is actually something of a point of pride in the DotA2 community. They revel in the steepness of the learning curve as a defining feature of what makes their game interesting and fair. Once you’ve picked a character in DotA2, the game then highlights different workshop accessories, which are alternate aesthetic models to customize every part of your character from boots, to gloves, to swords. These items don’t have any impact on the game and cost small amounts of money to buy, generally from $.99 to $4.00 USD.

In LoL, they have 126 characters to play, but new players initially only have access to a set of 10 of those characters they can play for free. To permanently acquire a champion you can spend money, generally between $4 and $10 USD, or the in-game currency called “IP” that you gather slowly by playing matches. Newer characters cost the most, while older characters are cheaper. Each week another different set of 10 champions will be available for free so if you want to keep playing the character you liked you need to buy them. You can also buy aesthetic variants called skins since they replace the whole model for your character.

With HotS, there is a similar free rotation system, but with only 5 characters available out of 39. The game also offers you a daily quest, which gives you bonus in-game money if you complete it, but requires you play either a character from a particular game world (World of Warcraft, StarCraft, etc) or from a specific role, which may or may not be available for free that week. DotA2 has mostly stopped adding characters, LoL adds a new character about once a month, and HotS is still new enough that they are adding new characters fairly rapidly with the stated goal of adding characters as long as the game exists. Though as we’ll examine in later sections, the more characters a MOBA has, the more complicated it gets for the designers to balance the game play.

The Othello Legacy

One curious statistic is that players connect with and hence prefer to buy humanoid characters over non-humanoid (such as blob or insect) characters by a statistically significant margin, even if the non-human characters are better. This is a key to looking at the ways that the companies try to convince players to spend money on the game. For instance, this statistic can be used to partially explain why DotA2 has many more non-human champions than LoL: DotA2 doesn’t have to sell you the character, just fun accessories like gemstone crowns and flaming swords, while LoL has to a deep financial incentive to get the player to emotionally identify with and thus acquire the character itself.

One interesting way to examine the representational design decisions of MOBAs is by taking stock of what kinds of characters are made available. Given the innumerable issues with diversity in mainstream video games, whether it is gender, race, age, or disability, for the purposes of this article as a series of starting places for further research, the easiest statistic to count is the male to female representation of the playable characters.

In DotA2, there are 89 playable characters that are male, 18 that are female, and 3 that have no assigned gender. For a closer breakdown there are 10 females that rely on “agility” and 7 on “intelligence” while there is only one female character who has “strength” as a primary statistic. Examining LoL, there are 83 male, 42 female, and 1 non-gendered, character. HotS has 27 male and 12 female characters. One choice that stands out in these numbers was that all three games generally assign a traditional gender to a character even if they are a strange floating eyeball, mutant insect, or energy being, something that would exist outside of our social paradigms of gender.

Compounding the already complicated conversation about diversity in video game representation, these three games are deeply rooted in the genre of fantasy literature. From Tolkien having the all the dark skinned men as part of Mordor’s army to World of Warcraft’s various fantasy races featuring accents and dances that correspond to non-white human societies, this genre has long had significant issues with racial representation and relegating non-white race to allegorical symbols (usually of the inhuman or monstrous variety).

Given the further implications of these tropes, purely methodologically it is still tricky to get a count of racial representation in these three games. Do you count “dark” elves as black? “Panda” people as Chinese? How about heavy drinking, wode-wearing, axe-welding, Scottish-accented characters: Dwarf or Scotsman? Personally, in all fantasy and science fiction I find that sort of allegorical mapping to be artistic laziness (see Michael Moorcock’s classic “Epic Pooh” essay, or China Melville and David Brin’s thoughts about fantasy cultures for an introduction to this line of avant fantasy thinking). But even leaving my bias aside, it certainly seems like a problematic implication that if you want to play a character that’s even vaguely darker-skinned you have to be a magic fairy-tale being or animal, probably with tusks or claws. Some of the many of the articles around the game Witcher 3 have looked as this issue, my favorite of which is excellently researched article by Luke Maciak titled “Witcher 3 and Diversity” ).

Possibly the most straightforward way to look at this issue would be to count how many actual human characters there are and their skin color/race. This means even the most humanoid demon, elf, or dwarf is excluded from this count. HotS has 10 human characters, and all are white/Caucasian. Counting racial breakdown in LoL is far more tricky, since they rely on a combination of fantasy and super-hero tropes, along with their nebulous lolore, make the line between human and fae more blurry (i.e. does adding a tail to an otherwise totally normal human make it non-human or is that just fan-fashion? Is “Southern Ionia” mapped to India or another Southeast Asian state, or nothing specific at all?), but for a rough count there about are 46 human characters of which there are 32 white/Caucasian, 8 Asian, 2 black, 2 Latin/Hispanic, and 2 from India/Southeast Asia.

DotA2 has about 22 human characters, of which 17 are white/Caucasian, 1 Probably-Mongolian/Central Asian (given the title Khan), 1 Latin/Hispanic, 2 Middle Eastern, 1 Asian, and no black characters. Looking at the character art closely, one interesting note is that in HotS, human characters tend to have exceptionally pale-Nordic skin, while in DotA2, the human characters tend toward a rather darker Mediterranean skin tone.

Correlating these choices of representation to player demographics would be the next massive step, but for the sake of space, it will serve to note that one unique facet of Riot Games is that they have been the only MOBA game company willing to share some demographic and design information with the general public (which is a small part of the reason this article skews slightly toward discussing LoL). It has openly said that “over” 90% of the 67 million global players of LoL are male and 85% of those players are between 16 and 30 (and interestingly, 60% are college educated, or are in college). There is no publicly available demographic data for player nationalities, but we can generally infer that the major locations where players hail from are the ones that have the official professional leagues sponsored by the company, which are: North America, Korea, China, Southeast Asia, and Western Europe. Though South America does not have a full status league, it has professionally organized LoL play, as does Turkey.

DotA2 is seemingly similar except it has such a large player base in Russia and Eastern Europe that they have an additional league there called CIS, but has almost no presence in the Korean market. It is unclear precisely where HotS will be popular, but the upcoming world final has the same regional breakdown as LoL.

In next week’s installment of “Demystifying Mobas & Esports” we’ll be staying with the characters. The focus will shift from artistic representations to examine some of the differences in core design philosophy between these three games. Each game has a very defined idea of how characters should be empowered to act, and what sort of methods of interaction the players should have with these digital pantheons.

Part 1 - Demystifying MOBAs: An Introduction to an Introduction

Part 3 - Demystifying MOBAs: The Pantheon in Action

Part 4 - Demystifying MOBAs: A Charming Stroll Through Flatland’s Battlefield

Part 5 - Demystifying MOBAs: PLAY - The Gory Farming of Glory

Part 6 - Demystifying MOBAs: A History of Speed