"Games are an alien art form" - An interview with the makers of Somewhere

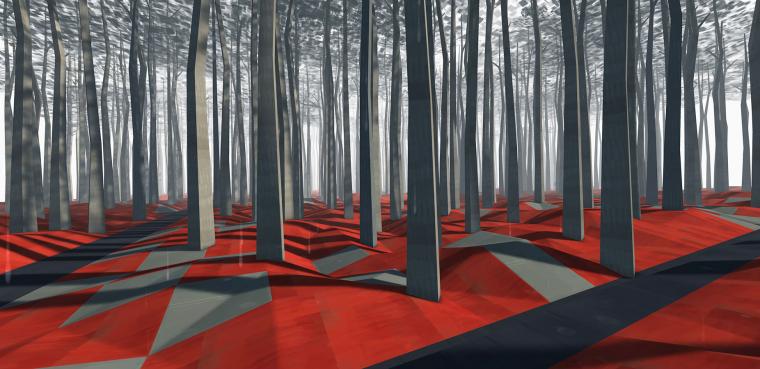

Some games are instantly recognisable as special. When I saw screenshots of Somewhere, an upcoming game by a small indie studio called Oleomingus, I was intrigued: The game's graphical style instantly reminded me of a cross between Introversion's Darwinia and Cardboard Computer's Kentucky Route Zero, the dev's tumblr-blog featured poetic background texts and just a few details about the tiny indie studio who develop their game as an "open collaborative" on the web and at Khoj, an artist-in-residence programme and venue near New Delhi, India. Details about the game, however, were few and far between.

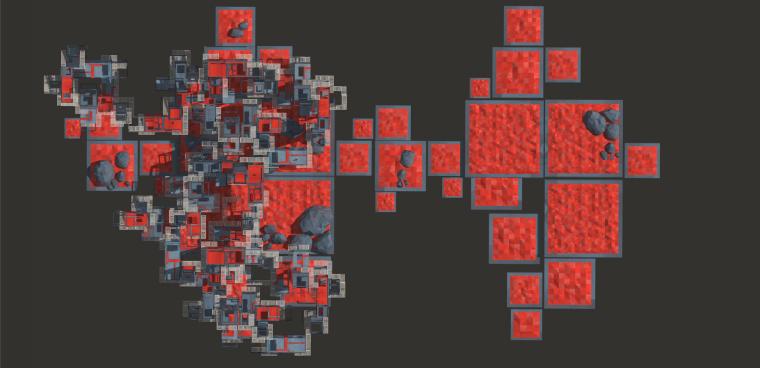

Dhruv from Oleomingus was kind enough to provide me with a deep glimpse into this fascinating work-in-progress. Somewhere is an ambitious project, and while there is no playable prototype as of yet, the existing pieces, art assets and design documents promise an exploration game, set in a bizarre town called Kayamgadh and neighbouring, otherworldly landscapes. "A player travels by becoming other people", Dhruv explained by email. "As you navigate identities, you realise that each person you become is a figment of another character's imagination and a part of yet another story. Somewhere is therefore, most of all, a collection of stories. A collection that spawns characters through which a player might comprehend this Gameworld."

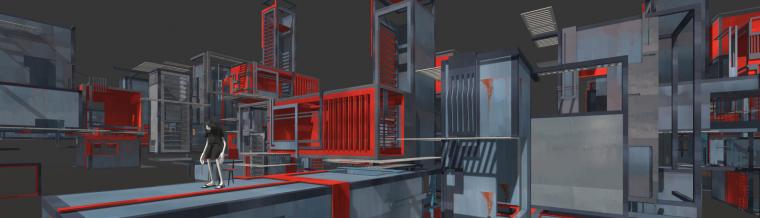

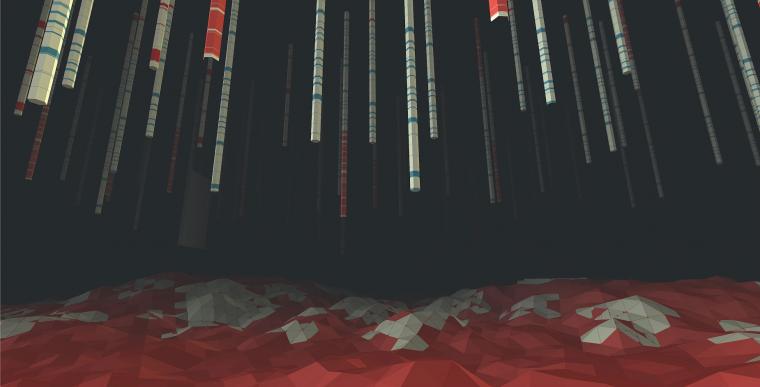

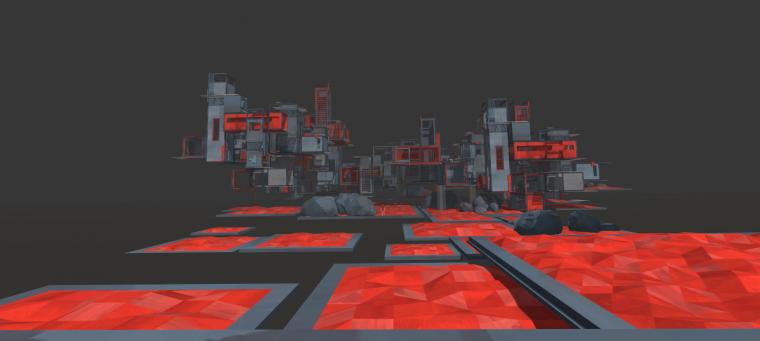

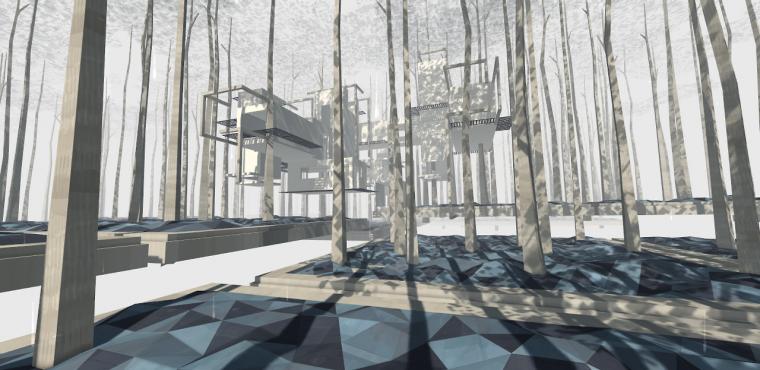

While the actual proof of the game will be in its playing, Somewhere surely seems to aim for ambitious heights in both abstract storytelling and the exceptional art it features. I have asked Dhruv a few more questions regarding the creative process and Somewhere's inspirational sources by email. Here are his answers - and a few spectacular screenshots to whet your appetite for the game.

Somewhere is quite ambitious in many regards. You have stated previously that the game is interested in exploring serious themes like colonization and India's actual history of independence. Can you explain? Will Somewhere be a “serious game” at heart?

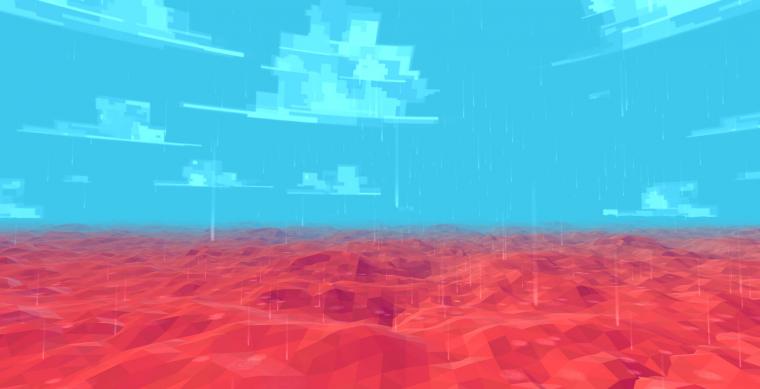

Somewhere is actually not a game about colonialism - it's about a time of flux. In the creation of a country pockets were left untouched, pockets that tried to interpret the sudden modernity of Independence through the lens of their entrenched beliefs. It is in one such pocket the game is set in. This is a game about people and their lives, about absurd encounters and stories that are lost. The game itself is a formal exploration of storytelling and investigates the conflict that arises from the subversion of the role of a storyteller in videogames. You are searching for a person. a person who has taken refuge in the mythical town of Kayamgadh. For a large portion of the game you try to reach this town as you travel through physical space and time.

Somewhere is a didactic game, but not a serious game. To players perhaps it will appear to be an uninvited window into the lives of other people.

You have cited Dear Esther as an inspiration, a game relying heavily on obscurity, on interpretation and ambiguity, a concept that reminded me of Eco’s “open work”, a piece of art made for interpretation. Is Somewhere going in this direction as well?

It is interesting that you compare this method of interpretive storytelling with Umberto Eco's definition of open work.The retelling of our story by the player as an author is a form of improvisation, a re-telling vastly removed from the one originally intended. We are not looking at art forms in general, but specifically at literary works, so my understanding of opera aperta translates simply, within the game, as the ability to craft interpretations around your experience of the story.

A bulk of our works looks at how other stories, which allow such interpretation, are traditionally told. Our (Indian) mythological epics, which are essentially composite stories, allow precisely this freedom. which has lead to a staggering complexity of religious rhetoric being associated with them. These structures, which allow variable character interpretation, and a malleable plot emphasis to reroute the fulcrum of the narration, can also be found in folk lore, and street theatre. An example : RK Narayan's Yayati from Gods Deamons and others compared to Girish Karnad's Yayati.

In terms of structure our strongest influences lie in the nonsense works of Sukumar Ray and Lewis Carroll or the theater of Girish Karnad, or the absurd world of Sarnath Banerjee. Or from within the beautifully told My Name is Red by Orhan Pamuk.

At the same time, Dear Esther is one of the most linear and basically non-interactive games of all time, a fact that led to heavy criticism by some gamers. What’s your definition of “game”? Will Somewhere aim for more interactivity or gameplay than thechineseroom’s games?

Dear Esther manages to fall through almost all the cracks of Jesper Juul's definition of "game". The outcome of a player's action within Dear Esther is certainly not quantifiable, and while the pieces of narration are a rule based response to the player's exploration, their random occurrence makes them obscure as a system, and unpredictable as far as the player is concerned. Moreover the inevitably of the game's outcome is absolute (its lineraty as you mention). But Dear Esther is a game, precisely because of the above stated reasons.

I argue that Dear Esther is not a game that can exist independent of the all the previous first person games, that have been been made before. With its familiar first person controls (it even has a flash light), visible continuity of its level design, where you can almost always see portions of an area you haven't yet explored, and its deliberate but constrained visualisation of environments within its narrative, Dear Esther manages to be just long enough to build upon the learnt practise of engaging with a videogame, and using that behaviour to tell a very different story. Since it calls upon the player to engage with the medium, with the same assumptions that a player would ordinarily approach another game with, it is a game and not interactive fiction.Somewhere on the other hand, is not built upon any repository of learnt behaviour. It of course derives its controls strongly from first person stealth games, but the intrinsic behaviour of these actions

(and controls) within is very peculiar. To us as a studio, games are mediums of storytelling first, but we believe that stories cannot be narrated with a gameworld for a game is not a narrative medium, and can only create (rule based) instances. Therefore Somewhere is a storytelling experiment, based solely on gameplay ( where dialogue is gameplay, and not narration, a fact evident in the dialogue flip mechanic ). So yes, Somewhere will definitely be significantly more interactive than Dear Esther. While I find Dear Esther an inspiring game, Somewhere bears very little similarity to the same.

Some of the writing on your tumblr on Kayamgadh, the city or region where Somewhere is set, specifically reminded me of the South American magical realist writers’ style. Are there any special authors you aspire to?

The stories and the people are the sympethetic characters of malgudi from RK Narayan's world or the people from VS Naipaul's books, or Chihua Achebe's disillusioned men, and the Parsees of Rohinton Mistry's world. The magical realist influence that you see in some of the writing, is from Haruki Murakami's work that celebrates trivial magic, and the works of Luis Borges (Aleph and Fictions).

But one of my strongest influence thought the game has been the work of Italio Calvino, and his book The Invisible Cities.

I found an interesting quote on your blog: “interactions within a game cannot supplant storytelling, because the storytelling system does not exist within the game world, but inside a repository of experiences that each player carries inside their head. But the interactions that reveal the story ( the instances ) still work within rule systems that determine game play. So to be able to tell complex stories, is it necessary to create an extremely large rule set that might simulate all manner of instances? or perhaps create a rule set that can create specific portions of the story through these instances.” Well? Did you find an answer yet?

We discussed the structural merits of using a particular form of game mechanic in a longer email, from which this quote is taken.

Sadly, the matter, for us, is still unresolved. But for the purpose of our game we assume the above excerpt to be completely true. The game mechanics take into account this insidious nature of a player's presence and the disproportionate control a player normally has in the telling of a story. Perhaps they balance these abilities.

Most games only look to movies and try to emulate a “cinematic experience”, but you seem more interested in emulating a spatial, architectural experience, quoting Lebbeus Woods and, at least to my eye, Frank Lloyd Wright, too. What are your most important inspirations in that regard?

While our literary references for the gameworld are varied, the architecture is strict and limited. Modernist-machine-like, broken and conflicted, it is electronic parametric and incomplete, informal, absurd and repetitious. Lebbeus Woods' War and Architecture (his work in Sarajevo) , or Archigram's mechanical cities inform the visual aesthetics. And so does Superstudio's continious space and other experiments or Daniel Libeskind's machines or the cybernetic work of Jhon Faser and Gordan Pask and the work of Lars Kordetzky.

The machine aesthetic, combined with the geometric forms is a direct result of these quasi-modernist references. The Lloyd Wright imagery is unfortunate, for I have never used form clean enough suit the traditional modernists, the closest reference would perhaps be Le Corbusier's poetic but brutalist work.

I am glad you mention Kentucky Route Zero (the article you have linked to is wonderful by the way), for it is a game I wish I had built. That game almost does everything we want to do within Somewhere: the evocative visuals, the literary references, the carefully calibrated use of nonsense reveal a very disciplined use of literature within the structure of a videogame. A similarity it shares with Dear Esther, where limiting the player's influence upon the world translates wonderfully to the ambiguous narration. I also love Dear Esther for its level design, which is so deliberate and linear without removing from the experience its alienating sense of a desperate exploration into the bowels of the island.

Videogames are already an art form, they are a medium capable of expression and engagement. But they also derive character from the very strong subculture that creates it, and the incremental nature of their creation. Most videogames are strongly dependent on the ones prior to them in their execution of their mechanics or their technology, information and techniques which is freely shared and made readily available. This is not an aspect they share with the art-world, the blurring of authorship, a democratic appeal and (especially with indies) the manner of their dissemination, make videogames distinct from the practises of an established art-world, while keeping them well within the definition of an artistic practise.

So, I believe that while that while the formal approach to art, its documentation and its study has a lot to offer games, it is with caution that one must accept all the entrenched modalities of the art-world itself.

The sheer oddity of Somewhere's creatures reminds me a bit of ACE team’s Zeno Clash, which borrows heavily from Hieronymus Bosch, Alejandro Jodorowsky and Antonio Gaudí. Do you know the game? Do you also aim for a similarly bizarre atmosphere?

I haven't played Zeno Clash, but I have see some rather wonderful visuals from the same. I do believe that working outside an entrenched sub culture like gaming, while being able to observe and follow the same can very easily translate to interpretation of games and their themes differently. Games are an alien art form, and unless the creator can embed familiarly in subject or visuals or method, games can often be rather alienating.

ACE Team, the makers of Zeno Clash, hail from Santiago, Chile, a place also not widely known for its game devs. Do you think that this geographic position on the very margins of the games industry, this outsider perspective can also be seen as an advantage?

Working as a game studio at "the fringes of a game community" is interesting. While the general reception to our work has been one of disinterest amongst people we normally associate with, we are now finding roots into a genuinely interested community that seeks to look at games differently.

Our experience at Khoj was an example of the same. People we worked with at Khoj (an organization established to support contemporary art and emerging artists in South Asia, based out of New Delhi, India) and the artists we met were not only interested in exploring games as a valid medium of complex expression, but were also intimately familiar with development methods and the technical complexities involved. Khoj managed to bring together people as varied as filmmakers, authors, visual artists, and literature professors, who are working on and writing seriously about videogames.

When I travelled in India a few years ago, I was blown away by the sheer architectural diversity and uniqueness, from baori stepwells to the giant forts and - I hope you’re not offended by this assessment - the sheer madness and chaos of Indian cities. Yet Somewhere, despite being set in India, shows very little of these landmarks. Why is that?

You mentioned the chaos and the iconic architectural styles of India, and the step wells that you mention are a particular feature of western India, where the story is set. But in both the scale of the story and its sense of place, we are trying to limit the iconic and abstract the familiar.

To a person living in a hutment clinging to the walls of the fort, the fort is not architecture, it is as landscape. amorphous and trivial.

No. We are not an "Indian" game studio, though we are predominantly based in India, and Indian social concerns often create our stories. People we work with are from various countries - from India, the US and Russia.

What does define us is that we are all outsiders to both game development and videogame communities. We do not develop games because we are fanatic gamers, nor do we perceive games through a history of having played the traditionally iconic ones. We work on videogames as an alternate storytelling medium.

The team working on Somewhere is varied, both in regard to skill as nationally: Salil is a chemical engineer by profession, but he is a trained vocalist and pianist as well, and is currently studying composition at Berklee college of music at Boston. Somewhere in its current form is programed by Kevin Vargas. He is a programmer and musician from Los Angeles. He started working with us a few months ago, and has already with spectacular skill programmed much of the charcter flip mechanic and AI within the game. Austin Ashley from Detroit works on the animations for the games. I believe he is studying animation. We have also begun working with a Russian composer, Konstantin. Oxygen is being programed by Sushant, a student of programming who also worked on Mosquito and the gravity mechanic for Somewhere. He is also now working on a new collaborative project we have just begun.

I myself am a final year student of design. I specialise in a form of architecture that studies the behaviour of temporary construction in public spaces. I create the environments in Sketchup and compile the game in Unity.

We have been working on Somewhere off an on over the past year, and development has accelerated since Khoj. We plan to turn full time, in December (after I finish my thesis). We would then be able to create a detailed but small prototype for the game, which we will use to perhaps generate funds for developing Somewhere further.

We will finish Oxygen by December, we are not sure if we will openly release Oxygen or not, that is something we will decide as we arrive closer to completion. But the game will be available to our Kickstarter backers, and some portion will be playable on our webpage.

Meanwhile we have begun two rather ambitious collaborative projects, with people we met and worked with at Khoj. One is an RPG game based on mythical characters from Malaysian folklore, for which we are crafting a statistical combat system. And the other is an open world exploration game in part inspired by the people associated with a recent archaeological find in Goa.