SPIEL/FILM: "Videogames are all about real time." An interview with John Hyams

SPIEL/FILM is a series of articles by Ciprian David and Rainer Sigl on the differences and similarities between and the convergence of two media - games and movies.

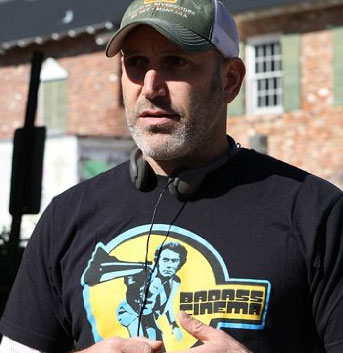

It is no exaggeration to state that John Hyams is a cult director in the making. The son of Hollywood veteran Peter Hyams has already been called the best action director working today and has proven his extraordinary talent in his few full-length genre movies - a talent which has as yet remained under the mainstream's radar. Discerning critics have compared his work on the "Universal Soldier"-series with that of influential cult directors like John Carpenter, Gaspar Noe, David Cronenberg, Werner Herzog or David Lynch:

Universal Soldier: Day of Reckoning is the most exceptional movie of 2012 in part because it has no right to be as good as it is. ... [Hyams] made a strange, haunting, sometimes even beautiful odyssey that lingered with me more than any American movie in recent memory. Despite a few surprised critical notices (like this and this), [Universal Soldier: DoR] was too disreputable to be talked about during awards season, but that’s okay. Anything this unusual deserves its own conversation.

Ciprian David and myself were thoroughly impressed with Hyams' masterful resurrection of an action franchise long thought irrelevant. His two offerings in the "Universal Soldier"-series have taken Emmerich's original series to its most extreme, with fatalistic and hypnotic intensity. Most fascinating for us here at VGT was both movies' aesthetic and thematic relationship to video games - from "DoR"'s ultrarealistic FPS-opening to "Regeneration"'s final "multiplayer battle" feel and location, both movies appeared deeply related to the younger medium's aesthetic and content. (Ciprian's take on DoR's relation to games - in German - can be found here.)

We decided to ask John Hyams himself a few questions regarding his work's relation to video games, and he was kind enough to respond.

First things first: Do (or did) you play videogames yourself or is the fact that, watching DoR, both Ciprian and I were reminded of a certain videogame aesthetic just a case of accidental convergence?

I actually don’t. I played video and arcade games growing up and have played some games here and there (messed around with Call of Duty, Grand Theft Auto, Splinter Cell, among others), but it’s ultimately a door I’ve intentionally kept closed for fear of getting sucked into it.

However, I love videogames from afar and admire their aesthetic. And while I haven’t spent a great deal of time playing videogames, I’ve certainly spent time watching and studying them.

As a director of the action genre, do you think that there is a closer relationship between your genre and games, where player action is central and narrative is often not as essential, but merely used to frame the action?

It’s an accurate observation and certainly something I had in mind when I directed Universal Soldier: Regeneration – there’s a point in that movie where the narrative becomes secondary to the characters advancing from one “level” to the next. Suddenly exposition and dialogue are no longer necessary to convey the information. I thought of the final act as a multi-player environment where one character will emerge victorious.

The “Universal Soldier” movies seem to play with videogame aesthetics in a few regards - the first person view in DoR’s exposition, the third person “over the shoulder” cam, the one shot sequences. Did you intend to emulate these perspectives?

"The videogame aesthetic is about a subjective camera and continuous, unbroken takes."

This is precisely how videogames have influenced my work. As you just stated, the videogame aesthetic is about a subjective camera and continuous, unbroken takes. In videogames you don’t see what’s around the corner until you get there. I am a big proponent of subjective storytelling and I think about point of view for any given moment or scene, not to mention the entire film.

From my perspective, "Children of Men" is a better example of the videogame aesthetic that anything with quick cuts. To me, quick cutting is a commercial aesthetic, because commercials deal with condensed time. Videogames are all about real time.

Very recently, George Lucas and Steven Spielberg have ridiculed videogames’ ambitions as a storytelling medium. On the other hand videogames seem to be influencing at least some movies, not in regard to narrative, but aesthetic. Do you agree?

I think they make good points, however in my opinion it’s unnecessary to compare the two. The purpose of a videogame is for the audience to control the narrative, which becomes a virtual experience. The point of movies is for the audience to be told a story. There’s a great joy in both experiences and one should not supplant the other. The experiences one has playing a game are visceral and call upon your reflexes, strategy and gamesmanship, in the same way that playing a sport calls upon those instincts.

That said, if David Fincher or Alfonso Cuaron are telling me a story I don’t have a need or desire to take part in the narrative – I want to sit back and be surprised, amazed, frightened or moved. It’s about being a passenger, not a driver. The world needs both of these experiences and one should not work too hard to be the other.

There is, after all, a common audience, familiar with both movies and games. Do you think cinema and videogames could profit more from each other?

They should profit from each other in the same way that a graphic novel and a film should profit from each other. It’s my hope that both art forms can continue to evolve without the need to compare themselves to each other – there’s more than enough room for both. I like watching movies, reading books, and watching sports, yet I don’t feel any need to combine those forms of entertainment.

There’s a narrow path between depicting violence/offering violent game content and making the viewer/player feel it or even contemplate the implications of this violence. Do you think that there is a fundamental difference to movie violence vs video game violence?

The fundamental difference is that one is perpetrated by the player while the other is witnessed. In either case violence can be glorified or condemned. For me, I think it’s important to depict violence responsibly, and my definition of “responsible violence” is when it is shown to have consequences. And this has nothing to do with a moral position, because I don’t believe that violence in movies or video games has leads to violence in real life – it’s a reflection of real life, not a catalyst.

But to me it’s strictly about good storytelling. It doesn’t mean it can’t be done in a funny way (Pulp Fiction, Raising Arizona), it just means that it has to be dealt with honestly. If a guy gets hit with a lead pipe it should leave a mark.

Both games and the action genre usually deliver "power fantasies". But “Regeneration” and “DoR” can also be read as shocking portrayals on the effects of violence on the human soul. Do you think genre movies and games as well should generally try to offer more than simple wish-fulfillment to their viewers? Do you see an added responsibility for the creators of this kind of entertainment?

I think there’s plenty of wish-fulfillment entertainment out there and if you asked any studio exec they would agree with that statement -- the Hollywood word of the week amongst execs is that movies should be “aspirational”. I agree wholeheartedly with your statement that Regeneration and DoR are about the effects of violence on the perpetrators. That speaks to your previous question – I believe that violence is something that changes people. Victims of violence are forever changed and shaped by such an event and the same goes for the perpetrators.

"Breaking Bad" has done an amazing job of taking this idea and turning it into compelling storylines. How many times have we seen movie cops kill bad guys and then crack jokes and forget that it ever happened. I find that hard to believe. If I killed somebody, whether or not they deserved it, I’m sure I’d be haunted by it for the rest of my life. In the case of Hank, after he kills bad guys in gun fights he suffers post traumatic stress. I thought that was brilliant and unexpected and just great storytelling.

Finding truth in characters is what storytelling is all about. So, to answer your question, it’s less of a moral responsibility and more of a creative responsibility.

“Regeneration” in particular led me to the interpretation that the universal soldiers can also be read as gamers' avatars... In fact, game players’ avatars are as immortal - and also only have as limited (and as destructive) avenues of interaction with their world - as the universal soldiers themselves. Would you agree with this interpretation? Combined with this observation, do you see the danger of games desensitizing their audience?

"I don’t believe violence depicted with consequences will ever desensitize the audience."

I do agree with that interpretation. The point of the "Universal Soldier" series was about the government playing God and creating real life avatars, or drones even, to carry out their dirty work. And what happens at the end of "Regeneration" is that the creations decide to keep fighting even when the war is over.

As far as desensitizing the audience, I don’t believe violence depicted with consequences will ever desensitize the audience. In fact, the violence I’ve created is meant to shock and repel the audience, to almost make them look away. I do that not because I’m making some moral statement but because I’m trying to move the audience and keep them engaged, and sometimes the way to do that is to make them nervous or uneasy.

To me, PG-13 violence is far more irresponsible and makes violence seem clean and bloodless – without consequences. So, if anyone is responsible for desensitizing the audience it’s the studios and their PG-13 movies. "Pirates of the Caribbean" makes violence seem fun -- "Reservoir Dogs" does not.

In many of the interviews you gave on "DoR" you talk quite a lot about filmmaking techniques and compare your strategies with other directors’ takes on making things happen in film. This made me wonder if you, when watching a film, generally perceive how it is made with an intensity comparable to the way you dive in its storyline, dramaturgical flow or fictional world.

I guess the best way I can answer that is that I’m just as interested in how a story is told than in the story itself. I’m interested in certain filmmakers and what they have to say. If Spike Jonze makes a movie about somebody eating a sandwich I’m going to be very interested. And the opposite is true as well.

One of the more indirect but still very present aesthetical reference to games I saw in DoR was the use of light. It variates from almost clinical high key/low key contrasts in the beginning through noir (as John gets back home from the clinic), through several exotic environments, but very often you have him almost bathing in this very dense light that floods the image. This light feels very expressive and quite often very material, almost tangible - in a videogame one would often think it would be asking for the player to aknowledge it in it’s material perfection. Could you tell us a bit about how your decisions in this matter occured?

The point of this movie was to tell the story from the perspective of the monster. Therefore, we as the audience only know as much as him (which isn’t very much) and we perceive a reality that turns out to be somewhat of a construct. Therefore, DP Yaron Levy and myself decided that the look of the film would reflect our protagonist’s heightened perception of the world. We kept the light sources in the frame, and let them strobe and breathe to imply the state of hypnosis that our characters existed within.

What I loved very much about DoR was the focus on material, on objects, as storytelling agents. The mirrors especially - wherever Michael Mann or a videogame designer would have placed screens, you place mirrors. I came to believe you are deliberately constructing a conflict between the materiality of reality and its virtual dimension (with versions and upgrades of memory packs and stimuli and so on). Do you agree? Is the film advocating an analog part of the world?

I like that interpretation. I would say that the movie is certainly about identity and the questioning of one’s own reality. Therefore, we have several scenes where our protagonist looks himself in the mirror – the first time it’s done in first person POV, so we are effectively telling the audience that they will have to question their own sense of truth and reality in this story.

After that, our character continues to look in the mirror, searching for answers. Each time, he discovers something different and each time he descends deeper into the truth which is also his nightmare.

Given these convergences between games and some aspects of your movies: What would you imagine a John Hyams videogame - of the UniSol franchise, or any other - to be like?

I would love to take part in the design of a videogame but I don’t think my goal would be to make it like cinema. I would focus on what’s at the heart of the videogame experience which is virtual experience in real time.

So, I would probably start with the idea of taking the player through a narrative in real time without the use of animations to fill in the story. In fact, like DoR, I would embrace the idea that you move through the environment, picking up clues along the way. Maybe it would be more like a choose your own adventure book, where the player could experience a completely different game and scenario depending on their in game decisions.

And turning that last question on its head: Given the increasing number of movie adaptions of popular game franchises, which one game would you want to turn into a movie?

I’ve been developing a videogame themed script with a producer and writer that isn’t about an existing game but very much about the gaming experience. The writer came up with a great initial concept, and together we’ve steered it into a direction that could be pretty cool. We’ll see how it shakes out.