"Seeking the dangerous sublime": An interview with Richard Whitelock on "Into This Wylde Abyss"

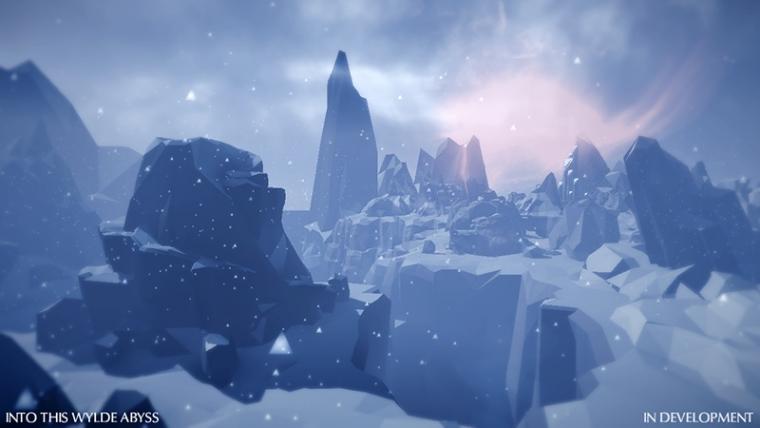

Into This Wylde Abyss is a work in progress described by its creator Richard Whitelock as "a short game about struggling to survive on a freezing island and what happens in your final hours, inspired by the dangerous sublime, Paradise Lost and AdamAtomic’s Capsule". Despite the very sparse information available on the game, I was at once fascinated by its visual style and the use of in-game photography.

Into This Wylde Abyss is a work in progress described by its creator Richard Whitelock as "a short game about struggling to survive on a freezing island and what happens in your final hours, inspired by the dangerous sublime, Paradise Lost and AdamAtomic’s Capsule". Despite the very sparse information available on the game, I was at once fascinated by its visual style and the use of in-game photography.There are a lot of survival games out at the moment, or in public development. Wylde Abyss is not a survival game of the strain that comes immediately to mind. There is no home making or food foraging. Instead, Into this Wylde Abyss revolves around finding the means of, and meaning in, staying warm in a perpetual and unescapably hostile environment. Fire is the central means around which the player survives and the Abyss changes.

I am a great admirer of what Robert Briscoe and The Chinese Room did with Dear Esther, and similarly Ed Key with Proteus. I was not only inspired by their work, it also helped me realise that there is an audience for games of this type. Whilst working at a large games studio, I initially worked on environment art and then spent some 6 or so years specialising in lighting and fx. So on completing Dear Esther for the first time I reminded myself of all this practice I had in this area. Swiftly followed by slight annoyance at having not started on something similar years ago. I then set out a long term plan for producing my own designs.

"If there is no struggle or journey involved in encountering a singularly unique moment then how sublime can it be?"

No matter how much experience you have, working seriously in games and computer graphics will result in constant learning. So realising I needed to familiarise myself with Unity fast, I begun iterating on smaller projects with the aim of making mistakes early. Learn your lessons quickly. Ludum Dare is a great motivator for this. After creating a minimalist Ludum Dare entry in 4 hours entitled "Don't Freeze" I was led to thinking about the 'dangerous sublime' and its relationship to so called "walking simulators". Dear Esther is a subtle, painterly game with bracing atmosphere and wide vistas, but no sense of danger in the world. There are reasons for the blanket around the player but it kept occurring to me whilst playing. We are guided calmly along treacherous cliffs, compelled to fall into caves and to stagger up exposed hills - what if this world was actually dangerous? If there is no struggle or journey involved in encountering a singularly unique moment then how sublime can it be?

Is there a correlation between the absurd in life and in transient virtual experiences? Do immersive worlds have the potential to allow artists to represent a form of awe that will be greater than any painting or landscape photograph? Into this Wylde Abyss is still at a very early stage, but it is step one in a series of experiments which keeps those questions in mind as pillars to build upon.

I was at once fascinated by Wylde Abyss's visual style - the almost abstract minimalism which puts atmosphere front and center. Would you agree that games in general are unique in that they allow players to __experience__ atmosphere, rather than merely be shown or told?

Part of the reason for the minimalist style is that of a greater plan I have for my projects. I am not a good programmer. So I am using Wylde Abyss as an opportunity to focus on creating a simple framework that enables me to make worlds in Unity without the burden of involved art asset creation. Atmosphere and lighting work comes quite naturally to me and I also have an appreciation for the "Low Poly" visual style. So I was happy for an opportunity to create a world that utilises it. Though "Low Poly" in this respect is somewhat of a misnomer. "Low Poly" suggests a focus on minimal polygon counts, but the polycount is typically far higher than any console of old could have handled. Instead it relies on high quality lighting and un-textured polygons. An excellent way of revealing the form and quality of lighting and material response.

It isn't just survival games that seem to be enjoying a flourish of development activity. There are also a great many "walking-simulators" of various kinds emerging. This is great. Though sometimes I can't help shake the feeling that I am looking at the narrated contents of an artist's environment portfolio. A portfolio compiled into a playable Unity or UDK project. If good enough, I would certainly be happy to pay for "just environments". But none the less I don't want Wylde Abyss to have that feeling. I want the player to feel active within an unique world that through exploring can be imprinted upon in multiple ways. A world that changes around them and reacts to evocative mechanics. The intent is to create something that couldn't be anything other than a videogame. That could only be made when the artist is also the programmer and designer.

Mode 7's games Frozen Endzone and Frozen Synapse, your previous projects, are stylish, but have their emphasis firmly on gameplay and game mechanics, while your personal projects appear to concentrate more on creating mood and maybe evoke or produce narrative. Which is more important to you personally, and why?

I have been friends with the founders of Mode 7 for most of my career and we have wanted to work together for many years. You are right that they are different art styles and different projects. I was only tangentially involved with Synapse but I took on the task of representing Ian & Paul's vision for Frozen Endzone. The main difference when working on someone else's game is striving to find that balance between art and design. We need to strike a brutal and exciting futuresport mood - but nothing can get in the way of communicating the information that gameplay requires. This is especially true for a game about reading tactical situations, so by far the most iteration goes on maintaining that balance.

For instance - in a Frozen Endzone stadium the contents of the play area recieves an incredibly thorough critique from everyone, but the vista beyond the stadium is pretty much left to me. I try to make them as epic and evocative as possible with the time available. The requirements of an art-lead game couldn't be more different. Sometimes an evocative scene requires obscuring information - this creates a markedly different reaction in the player. In Endzone the player's primary need is to appraise the situation and their opposition, in Wylde Abyss the player is lost.

The recently very popular "survival" games - single player ones like Don't Starve and Minecraft as well as multiplayer sandboxes like DayZ or Rust - merge sandbox mechanics with roguelike staples like permadeath or procedural generation. Will Abyss put its emphasis on survival as well, or will it rather follow the more atmospheric approach of first person exploration games? (What comes to mind atmospherically is The Snowfield.)

Into this Wylde Abyss isn't a survival game in the current mould. Maybe it isn't wise of me to refer to it in that way at all because it conjures images of tilling fields and running away from zombies. I do like the correlation with rogue-likes though.

"If rogue-likes could be art focused, then Wylde Abyss aspires to be an art-rogue."

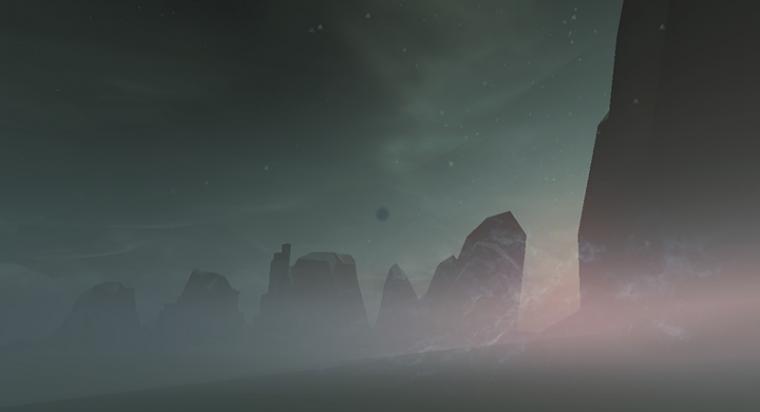

If rogue-likes could be art focused then Wylde Abyss aspires to be an art-rogue. It is definitely atmosphere oriented. But atmosphere and exploration are shallow things if there is no reason to explore. So the intent is to keep maintaining that enticing silhouette on the horizon and ensuring that it is represents both familiarity over time and expectation.

You are experimenting with a kind of "in-game photography" in that players will be able to haul a large format camera around to document - what exactly? And why?

"The most controversial idea I have is that the player can not see the photographs until the end of the game."

This was an idea I anticipated using for Lantern Slides. However I enjoy taking screenshots of the Abyss so much, I realised it would be incredible to not just support this, but take it a step further and represent a truth of photography in game. It will be quite simple to use in comparison to a real camera but considerably more involved than taking a screen grab. The procedure will allow me to reveal hidden aspects of the Abyss and process the results differently to the in game view. Perhaps using negatives of different types located by the player? The most controversial idea I have is that the player can not see the photographs until the end of the game. Anyone who has developed their own film will know what that feels like. You may with great difficulty take the camera to a cliff edge and hold an exposure for so long you perish. Getting the best images could take some sacrifice.

Why does the player character do this? Well it ties into the intended narrative theme. An individual seeking the dangerous sublime might well make photography a part of their expedition. Real photography is hard work and unpredictable. Equipment is a burden and moments are often missed.

Well, as for what to photograph - I will leave that up to the player. I love the idea that another player's photos might surprise me.

In my series "Screenshot deluxe" I try to document the interaction between gaming and photography. I would argue that games are recreational spaces, and that documenting the vistas, aesthetic and atmosphere of these places is just a natural extension of our modern obsession with photography. Would you agree? Do you think that games make good hunting grounds for photography?

Absolutely. There is an interesting conflict though. Photographers look for moments of interest within the chaos of the world. In games we are exploring a world that is itself constructed by artists. When executed at its simplest a kind of set design or virtual theme park. Game photographers have to make real efforts to excel when representing those moments - whilst recognising the prior art that made it possible. There is an axiom of photography I try to remember when shooting that might also be useful to game photographers: endeavour to take awesome photos of mundane things - not mundane photos of awesome things.

I need to ensure that Into this Wylde Abyss contains just the right amount of chaos for players to find their own framing points.

Photogrammetry is going to become increasingly common in both game development and the manner in which we document our world. There are already phone apps which use the technology in a simple way. The barrier for usage in games at the moment is the specialist software and very broad skill set required. And despite appearances, photogrammetry isn't exactly a time saver or trivial to execute. The results can be striking though. My plan is to to take the framework created for Into this Wylde Abyss and repurpose it for the more demanding world artwork of Lantern Slides. This will utilise photogrammetry - which will no doubt take up more of my time than low polygon models and I would rather not be thinking about game code much then.

The animated stills you mention are the Lantern Slides of the title. These are not created using photogrammetry. In fact the technique is simple, but also time consuming. It relies on my large photography portfolio. I convert the photographs by hand into windows - or portals - from which the world of the photograph is viewable in 3D. At the same time that world spills out to affect its surroundings with light and atmosphere. It's great to have a new medium with which to show my photography.

I am still formulating what exactly Lantern Slides will be, in much the same way that I have allowed the form of the Abyss to change as I work on it. It's often a mistake to set too many things in stone. I am not even certain if it will be a first person game or something intended for tablets, or perhaps even VR.

Lantern Slides is in some ways a reaction to the state of fine art photography as I perceive it. As much as I enjoy photography, I realised there was a futility to recreating things already done brilliantly in the 20th century on film. The results of which are then limited to a tiny group of people. Instead, why not utilise my photography and the fairly unique skill set I have been lucky enough to find myself with - to create new worlds that anyone with a computer can -actually explore-. This seems like a pleasingly empty map with which to chart new ground.

Certainly. I don't have a classically trained background in fine art or photography. But I am always finding new sources of inspiration - both from the past and among contemporaries. A few names from the top of my head would be Hiroshige, Sabastio Salgado, Ansel Adams & Gustave Doré.

One rather obvious inspiration for Into this Wylde Abyss is John Milton's Paradise Lost. Book 2 in particular ( It gets a bit dull towards the end ). There is one section which is seared onto my memory and might be familiar to fans of Phillip Pullman's Oxford fantasy trilogy. I love this - not only due to the atmosphere and anticipation - but also the manner in which each line lends itself to evoking a procedurally generated game world.

"To whom these most adhere

He rules a moment: Chaos umpire sits,

And by decision more imbroils the fray

By which he reigns: next him, high arbiter,

Chance governs all, Into this wild Abyss

The womb of Nature and perhaps her grave

Of neither sea, nor shore, nor air, nor fire.

But all these in their pregnant causes mixed

Confusedly, and which thus must ever fight

Unless the Almighty Maker them ordain

His dark materials to create more worlds

Into this wild Abyss the wary Fiend

Stood on the brink of Hell and looked a while

Pondering his voyage;"