Alt+Home: Basic Fears

As the technology became more advanced, horror games began to mimic horror films, using the same tactics and presentation that had been demonstrated to be frightening for audiences and adapting them into gameplay. Developers began to make use of technological advancements and put far more effort into creating realistic and polished graphics, unsettling atmospheric soundtracks, and environments engineered to be threatening. There’s nothing wrong with going to those lengths to create an immersive and bone-chilling experience, but how much of a game can you trim away while still retaining the basic elements that make it truly hair-raising? This is a question that some independent developers are seeking to answer, each in their own way.

Below are just a few brilliant examples of independent games whose creators have willfully withheld detail and bravado from their works, instead employing simplified visual imagery, clever writing, and the player’s own imagination to craft succinct and effective scary stories.

Great horror takes advantage of what the viewer can’t see: The shadowy figure skulking just out of sight. The sound of an ancient predator drawing closer through the darkness. Your imagination fills in the gaps, making the experience so much worse than if you could actually see the thing that wants to dismember you.

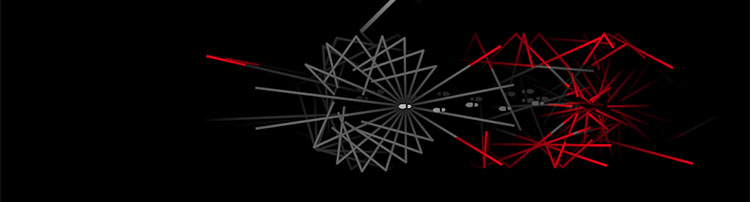

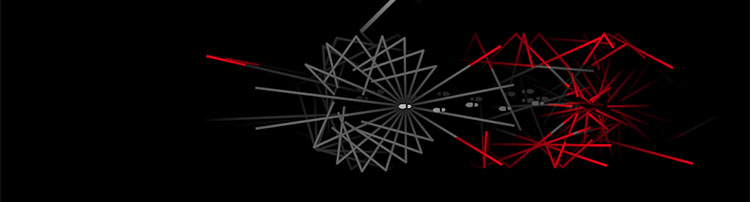

There are no environmental or character graphics in Dark Echo; as the player and ambient objects move through the world, they create sound waves as cascades of lines that fade as they get further from the source, but reveal the constraints of the environment as they bounce off of surfaces. The player must navigate the game’s levels using only these reverberations. Audio cues play a major role, as there is no music and very little ambient noise to underscore the sound of your footsteps plodding through the darkness. There are unseen creatures lurking in the darkness that give off distinctively menacing red lines and a low, unearthly roar as they pursue the player. These beings are attracted to sound, so if you stop moving, the creatures do as well. You’re going to need to move sometime though if you want to find the exit to each maze, so you’d better make a choice between trying to tiptoe silently through the darkness, losing your ability to spot traps ahead, and making a break for the exit, hoping you’re faster than the thing that hunts you.

You’re piloting a tiny boat through a rainy, murky swamp, the darkness pierced only by the faint light of the lantern affixed to the bow of your vessel. All of the trees look the same, and you don’t know what direction you should be facing, but it doesn’t matter just now, because something is stalking you through the mist; just out of the corner of your eye, you spot a row of spines piercing the surface. Your hair stands on end and you tighten your grip on the single spear in your possession, preparing to hurl it into the gloom and hoping that it strikes true before you have a chance to find out what’s in the bayou with you.

Bayou looks like a grungy watercolor painting, with a grayscale palette accented by crisp strokes of stark black and white and a cloudy overlay that functions as the oppressive ubiquitous fog of the swamp. The gestural, impressionistic look of the graphics are a departure from many horror games that attempt to depict space as realistically as possible. Instead, your imagination fills in the details of your surroundings, and as anyone who has had the childhood experience of hiding from shadows gliding across their bedroom will tell you, imagination can be terrifying.

A Night In the Woods by Amy Dentata

Playing A Night In the Woods feels like reading a spooky story by flashlight in a treehouse on a cold, windless night. The atmosphere is unnerving on its own, but it’s the creeping sensation brought on by each page you consume that really sends a chill down your spine.

The game looks like any number of 90s PC roleplaying titles at first glance, the pixelated 3D world enclosed by a bracketed wood frame, flavor text and inventory information floating in the margins. Because of this resemblance, and the overgrown highway you find yourself traversing at the start, you expect danger and terror to be waiting for you around every dark, moonlit corner.

It’s freezing outside; you’ll need to build a fire. Exploring further down the road, you’ll come across a series of dilapidated structures, and scattered nearby are old newspapers, books, and discarded notes passed from one unseen resident of these shanties to another. Reading through these materials as you gather them for your fire reveals the story, each text elucidating a little bit more about what has become of this world. Searching through the trees to find just one more newspaper or weathered tome will motivate you just as much as your desire to survive the night.

You find yourself in a tiny village, staring across a sun-scorched desert valley with gigantic, impossible structures silhouetted black against an orange sky. You hear the wind gusting lazily across the flat terrain, a faint whistling echoing from what seems like every side. Behind you a hulking pyramid looms, huge and menacing. Amidst the tiny shelters you spot a hovering polyhedron that glows an inviting green against the harsh umber background. As you step forward and touch it, a haunting discordant tone rings in your ears, and a voice begins to echo across the sands. This will become your grim guide as you explore the landscape and uncover its unsettling truth.

Like A Night In the Woods, the creeping dread comes not from monsters or jump scares, but from uncovering what’s already happened through the haunting monologues you’ll uncover as you explore the large, reflective stone objects jutting out of the otherwise featureless landscape. The real truth about this place, about your role in the story being unfurled to you piece by echoing piece, is yours to discover as you follow in the footsteps of the unseen who have gone before you.

Imagine waking up in the middle of a dark, moonlit forest to the sound of distant sirens and your own panicked breath, skeletal tree branches stretching together over your head. This is how Hide begins, depriving you of context and instruction but not wasting any time putting you on edge. You won’t know why you’re there, but you can hear something closing the distance behind you, heralded by a sweeping white light and a grunting voice that sounds vaguely like speech. You follow your instincts and begin to run, your footsteps crunching through fresh snow at a rate that will never feel quick enough.

Hide’s 3D graphics are pixelated almost beyond recognition, turning the world into an abstracted assortment of black-on-white shapes. This style reminds me of being stranded in strange surroundings without my corrective lenses, an experience that gives me an intense feeling of helplessness and panic just to imagine. By the time your pursuers get close enough for you to make out any semblance of form, it will be too late.

As with any form of media, there’s no perfect formula or checklist for crafting the perfect horror-themed game. Not everyone is impressed by fancy graphics, eerie soundtracks or gory and visceral special effects; likewise, some players won’t be satisfied by the nuances of more subdued or psychological thriller, just as some moviegoers prefer bombastic, overwhelming and shock-driven blockbuster fright-fests. Nevertheless, there’s sublime beauty in subtlety, and whether you’re a veteran of classics like 3D Monster Maze, or you revel in the most recent big-budget spookfest, if you are a fan of any kind of playable horror you’ll be doing yourself a favor by seeking out the experimental fare that has been patiently lurking in the shadows, waiting just for you.

Based in New York City, Kent Sheely is an intermedia artist operating at the intersection of video games, art, and pop culture. His work is an eclectic blend that includes game modifications, machinima, interactive works, glitch art, and live performance.

Raised by MS-DOS and Atari, Kent has been playing games for most of his life. While attending school for art, he realized he could combine his hobby with his creative work and enjoy both simultaneously. These days he is more inclined to play and write about alternative and experimental independent games, but still very much enjoys all forms of interactive entertainment.

When he’s not in front of a computer screen (as rare as that may be), Kent likes to read and watch all manner of science fiction, go hiking/camping, and hunt for hidden objects in the woods using GPS. Videogametourism has featured Kent's work here and here (German).