Alt+Home: A Matter of Trust

Video gaming technology matured and became capable of processing and storing more information, diminishing this reliance on the user to make sure the rules were being followed. Occasionally there would be exceptions; for instance, a game called Sneak ‘N Peek on the Atari 2600, which was essentially an electronic version of Hide ‘N Seek, was intended for two players and required one player to leave the room while the other found a hiding spot.

For the most part, modern video games don’t operate like this anymore. With the exception of player-created alternative rules, such as “Jeep Tag” in Halo, the software accepts physical inputs, makes decisions based on that data, and provides feedback. However, some independent developers have found ways to defer some of the rule moderation to the players themselves, getting participants intimately involved by turning them into crucial physical components of the games.

At a glance, droqen’s Asphyx looks like a standard two-dimensional platforming game. After you learn the controls though, on-screen instructions reveal that “this is a game about YOU. When your avatar is underwater, YOU MUST BE HOLDING YOUR BREATH.” There’s no way for the game to keep track of whether you’re following this rule, so you’ll be in charge of enforcing it yourself.

As the game progresses, this rule gets much more difficult to follow, and you will be tempted to cheat. Expanses of water will be deeper and more frequent. Platforms will collapse and send you plunging into the depths. Panic may set in. If you’re like me, and grew up with an intense fear of drowning, and by proxy a fear of seeing your game character succumb to asphyxiation, you might just decide to break the rules. Who’s gonna know, right? You might make it further in the game this way, but believe me when I say the game is much more rewarding if you don’t cheat.

Oh My Gorgons by Alan Hazelden & Sarah Marshall

Much like Asphyx, this game is about the player being in charge of one little rule, which may cause varying levels of discomfort when followed. In this case, you’ll be closing your eyes in the face of danger.

You’ll be navigating a maze full of monsters, including the horrifying Gorgons of Greek legend, which can turn you to stone if you look at them. In the context of this adaptation, you have to shut your eyes when your character is facing one of the Gorgons. Open them at the wrong time, and you’ll see a bright red screen with the words “You are dead -- press space.” If you’re being honest, you’ll press the spacebar and restart the level. This is a very short game, but the concept deserves extrapolation.

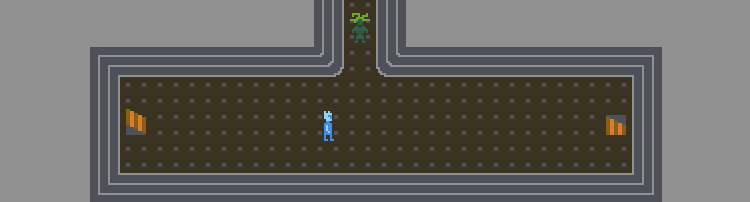

Have you ever sat in a circle with friends and shouted at each other while tapping furiously at your phones? That’s how it looks if you’re playing Spaceteam.

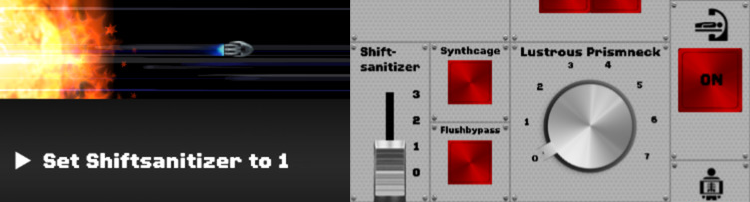

The premise of the game, played on smartphones or tablets, is that you and up to three friends are part of a starship crew. Each team member’s screen is populated with randomized control surfaces full of buttons, levers, switches, and sliders, each named using a different piece of technobabble (e.g. “Clip-jawed Fluxtrunions”). Your display will begin flashing instructions that need to be carried out by someone in the group within a time limit, however, you don’t know who has which controls, so the only way to ensure your instructions are carried out in time is to shout them at the group while listening for instructions relevant to your own set of controls.

It would be possible, of course, to cheat the system by placing all of your devices together and having one person follow all of the instructions. But that wouldn’t be any fun at all, would it?

Brace is a short interactive story whose ending hinges on trust between two players. The opening screen calls for only one player to be reading or taking action at a time, and for there to be no open communication between the two unless explicitly instructed by the game.

The narrative opens on a forest scene, through which the two players are running from an unnamed enemy. The pair will have to coordinate with each other without speaking, taking turns as directed, making choices through prompts on the screen and hoping their attempts to communicate will be received by the other.

It’s possible to cheat and either play by yourself, or maintain open verbal communication with your other player, but this would almost completely undermine the premise of the game and rob you of this unique experience.

Games don’t always have to be about “winning” or achieving a concrete objective. Player 2 is a text-based game designed around two participants, but unlike Brace, the second player isn’t actually present. This is a therapeutic tool in the form of a text-based video game, designed to help players overcome their interpersonal conflicts by having them visualize another person as a second player in the game.

As soon as you begin playing, you’ll be reassured of your privacy and safety, as you’ll be asked to be honest about your experiences and explain your side of the situation through text input prompts and multiple-choice selections. You’ll be gently guided through visualizing, processing, and resolving your feelings about the situation, almost like an interactive diary. From my own experience, the more honest and detailed you can be with Player 2, the more impact it will have; without you supplying the second player, without you pouring your own unique experience into the game, it’s just text on a screen.

Henry David Thoreau’s “Walden: The Videogame” by Dustin Smith

This title makes the list not because it’s particularly gratifying to play, but because it reminds me of what it felt like to be a rebellious high school student reading Walden and conjuring up grand plans of leaving society behind, moving into a shack in the woods and living out the rest of my life enjoying life in a simpler form.

There’s not much to spoil here. As soon as you click past the title screen, you’re presented with blue-on-black text that reads, “TECHNOLOGY BINDS AND CONTROLS YOU. YOUR FIRST STEP IS TO DESTROY YOUR COMPUTER. ONCE YOU DO THIS, YOU WILL BE FREE. DESTROY YOUR COMPUTER, AND YOU WIN.” This is the entire experience.

Embodying Thoreau’s mantra of “simplify, simplify,” the game's purpose is not to convince us to literally annihilate our technology; it’s a reminder that computers and other benefits of modern life should not be our only guiding force or the things on which we rely foremost. We should exercise control over ourselves and our environment, and always remember that our minds, our bodies, and our experiences are more important than the tools we use.

Based in New York City, Kent Sheely is an intermedia artist operating at the intersection of video games, art, and pop culture. His work is an eclectic blend that includes game modifications, machinima, interactive works, glitch art, and live performance.

Raised by MS-DOS and Atari, Kent has been playing games for most of his life. While attending school for art, he realized he could combine his hobby with his creative work and enjoy both simultaneously. These days he is more inclined to play and write about alternative and experimental independent games, but still very much enjoys all forms of interactive entertainment.

When he’s not in front of a computer screen (as rare as that may be), Kent likes to read and watch all manner of science fiction, go hiking/camping, and hunt for hidden objects in the woods using GPS. Videogametourism has featured Kent's work here and here (German).