Bridging Worlds: Workified Games IV

Even more importantly, I would also argue that the reason many of the video games I’ve been using as examples of workaholic tendencies are also beloved by fans is because they also contain vast swathes of leisure-oriented time. World of Warcraft is an excellent example of this dichotomy. Despite WoW’s attempt to reduce the grind, there are still many mindless repetitious tasks to do as play, from trying to earn reputation, to levelling alts, to waiting for item drops, to completing ubiquitous achievements. But a significant portion of what has kept so many of my friends engaged with WoW over the years is the large amount of time left for hanging out with friends, both real and virtual, in weird and wonderful fantasy towns; playing dress up and dancing; racing dragons over the desert; taking curious screenshots of beautiful vistas; and visiting old haunts (figuratively and also literally beating up ghosts). Even in high-end raiding, there are huge swaths of down time spent chatting, sightseeing, and playing pranks, not to mention the after-raid beers and story sessions.

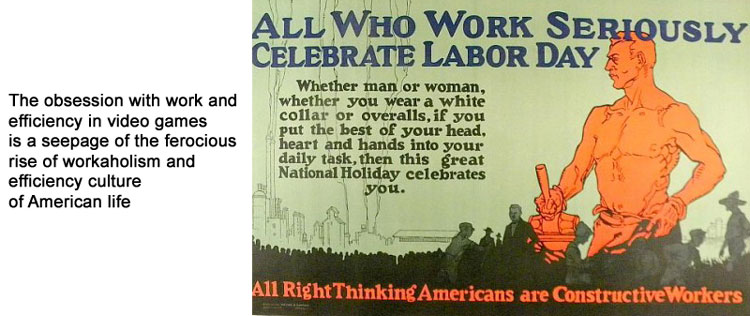

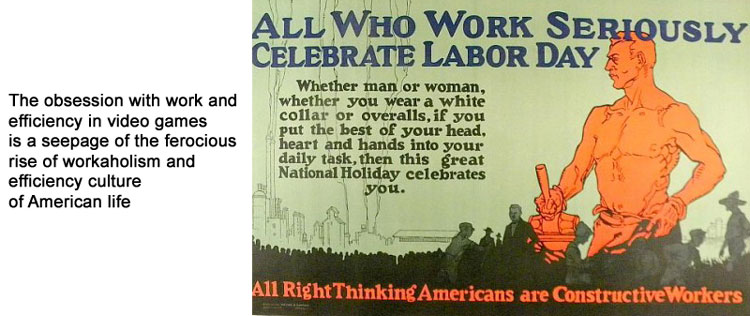

Through past instalments, I’ve made it clear that a large part of this obsession with work and efficiency in video games is a seepage of the ferocious rise of workaholism and efficiency culture of American life and the tech industry. But it also should be observed that part of the fans’ and designers’ obsession with rationalist work systems is very likely a conscious defensive measure to prove the worth of video games to a skeptical public. After all, for how many decades have video games been harangued and belabored by politicians and morally judgmental do-gooders as a vast “waste of time?” What better way than to dodge that massive, culturally loaded, criticism than to highlight the aspects of gaming that are measurable and work-like? Though my argument might, like leisure itself, be dismissed as frivolous, to rephrase it in a way that might interest investors, creators, fans, and advertisers alike: what I’m suggesting is that pre-restricting the market to only people who want to be part of a workaholic system, both as creators and players, is vastly limiting the potential size of both fandom and the industry.

To take a fresh spin on the insightful article “In Praise of Lando” by Julian Murdoch, part of my interest in workification’s limited narratives is rooted in the way that as we grow older our values and priorities invariably shift. Like a large portion of players, such as my gaming group, who still want to play but invariably buy fewer video games than we did when we were younger, a sizable portion of this decline might very well be attributed to our disinterest in games that replicate what we do in the rest of our time. That is, the kinds of games we find valuable and interesting have changed as our careers, relationships, hobbies, and even children have grown to prominence in our lives.

Simply put, many of my friends won’t play, meaning buy, games that have any grind or that feel in any significant way like the very work that keeps them away from their passions and families. Increasingly those whimsical, magical, and breathtaking experiences we found in video games are being reduced to one more cubicle desk, retail floor, or factory line. As such, this essay is a call for fans, marketers, investors, and developers to remember that leisure spaces, leisure systems, and leisure goals are as equally real to the experience of work in video games and are also equally part of the history of the games we loved. While efficiency experts want to “gamify work” to get their companies to be more profitable, we as fans and creators are working against the very thing we love, against the very moments that made us fans of video games, if we continue to “workify games.”

A counter argument for my observations about workified games might be that common leisure pastimes such as gardening or cooking a meal for friends could also be mistakenly viewed as “work-like” under my paradigm. In fact, thinkers like Kucklich have developed ideas such as “playbour” to talk about the kinds of work-like activities we increasingly do for fun. But, as the very need to generate a new term to separate playbour from labour implies, while there certainly is some work involved in planting some tomatoes in a garden or cooking pasta for friends those ideas are radically different in intent than the notions of monetized labor practiced by a field hand picking many tons of tomatoes or by the line cook making hundreds of plates of pasta at Applebee’s.

To reintegrate the term “play,” a word so critical to many theories of video games that I have danced around for more of the essay, philosopher David Steindl-Rast suggests, “Are the two poles of activity really work and leisure? If this were so, how could we speak of leisurely work? It would be a blatant contradiction. We know, however, that working leisurely is no contradiction at all. In fact, work ought to be done with leisure, if it is to be done well. What then is the opposite of work? It is play. These are the two poles of activity: work and play.” Because we’re paying attention and spending the exact amount of time needed to accomplish the work, most of us actually do our best work when we are doing it with a leisurely attitude.

Indeed, it is not work and leisure that are opposites, it is workaholism and leisure that are opposed. Indeed, as anyone who has ever gardened or cooked can attest to, one can assuredly work in a leisurely way. In fact, even though I’ve named Animal Crossing as a game that can feel workified, there are also many moments, such as fishing in the rain in the early evening, that evoke an idyllic beauty born of the small poetry of daily work. Albeit, crutching on some similar pastoral tropes, Stardew Valley’s pacing also shows how experiencing work can also be leisurely when presented in a way that has freedom from efficiency mandated grind.

The example of cooking can be used to clarify just how different feeling the same task can be when executed as a workaholic enmeshed in a system of exploitive labor or approached as leisure work. In a workaholic video game mode, your cooking experience might be hunting and killing hundreds of deer in World of Warcraft hoping to get the drops to make dozens and dozens of the same pots of deer stew so that one can level-up cooking to get an achievement or be high enough level to be allowed to make the food correct buff for a raid. In this way, WoW is much like working the line in a restaurant, where cooking is about completing task-oriented goals, set by a boss who represents a corporation, in the most efficient way possible so that something specific can be received for the time and labor loaned to the system.

Contrast that to leisurely cooking for your friends. Here the goal and the reward are the same, with the specific way you spend your time being set based on your own parameters (I’m making dinner; come at 8PM and bring wine). Sure, you might not have complete control since a friend might be like me and allergic to avocado, or you might get stuck at work later and need to have your friends help you make the food. Hell, you might burn the roast and have to order take-out. But like the combination of pathos and hilarity at watching a colony in Dwarf Fortress go up in flames because of a mad god running rampage, that very embrace of the fun and folly of human-ness is why leisure is such critical ideal to helping us understand our friends and our community in a more complete, intimate, and present way.

To return to David Steindl-Rast’s assertion that, “These are the two poles of activity: work and play,” this close relationship is also why video games that use play to consciously examine work can be so potent. Precisely by directly engaging in our dysfunctional obsession with work and progress, games like Cart Life, Office Simulator 95, or Papers Please, all of which are certainly not exactly “fun” in a traditional way, are so brutally effective as art because they lay bare the way work can dehumanize us. They also ask us as players to be aware of how easily we can become complicit in our own obsession with work as a marker of success. This should be a reminder, like the often dark hints in children’s playground games and fairy tales, that leisure is not always unbridled optimism, but an opening to a broader vision of the world.

Crucially the “busywork” and “grind” in games like Papers, Please is radically different than leveling a crafting profession in an MMO because it overtly teaches us how we can easily fall prey to the work-systems that exploit us. When you get a commendation from the central government in Papers, Please it is always fraught with meta-critical irony and criticism about what these awards for doing good work might actually mean. These types of games about the fetishization of work are also different in their expectation and respect for players’ time since they also do not demand nor congratulate us for spending vast swaths of our time with them. Most can be fully played and understood in a matter of hours, if not significantly less. They are work laid bare. Papers, Please and so many other DIY, alternative, and art games, encourage us toward a more complicated and interconnected understanding of how we exist in the world. They encourage us to be more present, which is to say, to break apart the linkage between busywork and status, which is precisely to be more leisure-oriented.

Indeed, two of the most effective indictments of the linkage of video gaming and work come from games themselves. In Unmanned, there is this intense moment of existential unease the first time a player comes home from piloting a drone and unwinds by playing a military themed video game. In a similar but broader way, it is crucial to understand that one of the overarching structural conceits of The Stanley Parable is that it is mis-applying First Person Shooter systems, controls, and exceptions, to an office environment. These video games are not without their legions of detractors, so it is critical to understand that, like telling a workaholic that “work isn’t everything,” merely by advocating for art and alt games that are oriented around leisure, presence, and criticizing achievements as progress, these works can be easily misconstrued as an assault on their values.

In Austin C Howe’s fantastic article reassessing the much-maligned Breath of Fire: Dragon Quarter, he pinpoints the communities longstanding hatred of the game as coming from the ways it constructs a world of powerlessness, poverty, and replicating the conditions of shift work. “It is consciously built to work against gamers’ expectations of the genre, and most of its design decisions prevent gamers from playing D1/4 (Dragon Quarter) the way they play any other JRPG.” This is not to equivocate, or to say that we should ever tolerate abusive or harassing behavior, but rather that from within the oft-progressively skewed community of artists and critics, it can be easy to forget just how radical and disruptive proposing such a de-linkage of work-progress and value can be. Hell, even within the more progressive elements of art and cultural work workaholism runs rife. Ask any artist or grad student when the last time they got more than 5 or 6 hours of sleep was! So it is always important to remind all audiences what Nabokov said, which should ring equally true for any fan cultural theory or of Final Fantasy VII, that “Texts we care about will both resist and reward us; not necessarily in that order.”

In ending, to borrow a phrase from Maria Popova, curator at of the philosophy blog Brain Pickings, right now it feels as though many mainstream video games are on a “productivity-guised flight from presence.” The combination of a focus on grinding productivity, flow, the value of efficiency, granular task-oriented structures, the constant inhabitation of job roles, and the hyper-focus on external achievements basically positions video game players as workaholics. With this workification comes all of the stress, anger, disregard for personal relationships, lack of paying attention, and xenophobia that is entailed by any sort of stress state. The work-obsessed mentality at the heart of so many video games is constraining our imagination for the kinds of games we make, the communities around them, the characters we imagine to inhabit the worlds, and even our ability to enjoy the games we play, because workaholism insidiously flattens everything to an endless loop of work and progress.

If we, as creators, investors, and fans, continue down the road we are on, video games will be just one more increasingly limited part of an economically focused system that wants to turn us all in to mechanical turks that pay to work our jobs. But if we can find a way to infuse leisure into our video game experiences, to remember to leave space to be present, we will be able pay better attention to the video games we play and to more completely cherish our experiences with them, both good and bad, both work and play. It is only through leisure and play that video games are able fully inhabit their role as a core part of what makes us human, of what inspires us, and of what teaches us about ourselves. Through leisure, video games can let go of the cycle of endless grinding achievement and be a force to help us appreciate each other more, help us understand ourselves more completely, and of what lets us see the world as a richer and more interesting place. After all, as Kierkegaard said so simply, “Of all ridiculous things the most ridiculous seems to me, to be busy.”

Extra special thanks to Zoya Street for the prompt to put my thoughts together on this series. Thanks as always to Rainer for being a home for my weird thoughts on video games and culture. Callie is once again a brilliant copy editor and makes sure you all can make sense of my ideas. Thanks to Alec, Sam, and Jason for informally talking through this with me, even if you don’t at all agree with me. Thanks to Han and Travis for helping out gathering screenshots to illustrate the series.

Links to the previous installments of "Workified Games": Part 1 Part 2 Part 3