Essays In Conversation 2: Remembering The Body While Playing Videogames

Kent: With my own work, some of the ideas come about completely by accident while I'm just goofing around. Was that essentially your method for coming up with the concept for the series Valhalla Nocturnes? Or did you kind of exert more control over the evolution of it? Tell me a little more about the inspiration and how the project built itself.

Eron: I need to provide a little historical context, because while the work seems like I stumbled on it, it actually comes from a really odd overlap with other things I was doing in photography at that time.

I had just finished up a project doing a massive screen drawings that were made by tracing the entire mouse movement from a League of Legends game. These traces of everything your mouse has done during that hour looks like a jumbled gnarled Expressionist etching. I was really interested in ways we could use digital imagining to see things we otherwise couldn't see.

At the same time, I was also photographing a lot of experimental and avantgarde music shows.

Kent: I was actually going to bring that up because I noticed that kind of similarity to your older documentarian photos?

Eron: I was trying to develop a language for these experimental musicians—and I'm not talking like crazy punk shows where people barf on the audiences—we're talking stuff like James Tenney, Pauline Oliveros, Cornelius Cardew. Maybe 60 minute pieces where minor tuning differences are exploited, that don't have performers doing extravagant gestures, that were very time-based, that were very subtle. Or this this ferocious heterodoxie of sound from free jazz. Making photographs of those kinds of performances is really hard!

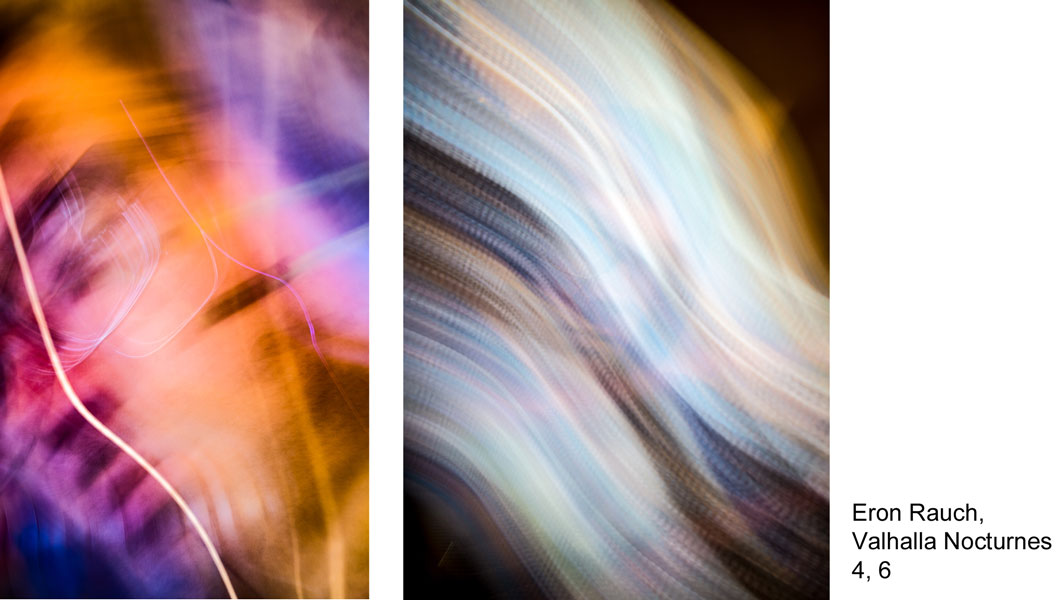

To do that work, I had been building this language of kind of really long exposures, manipulating the camera while it was exposing with focus shifts, double-exposures, multiple exposures layered on top of each other, or even covering half the lens with my hand. I started interacting with the camera in a very physical way to improvise along with the time-based bodily actions of the performers.

I was also just having a really crappy time in my life. So I’d come back from these shows half-drunk and be like sitting there playing League of Legends until godforsaken hours, just trying to kind of forget about everything and how tough life was. The camera always sitting next to me on the desk, because I had just downloaded the cards. I’m playing video games as the camera is there, and at some point I'm like, “Whatever. Screw it.” and started taking photos, using those techniques. Pretty quickly, I was like, "Oh, wow! This is really a radical evolution of the screen drawings. These techniques are even more radical when you apply in the video games." So it started more like accretion.

Kent: I think that is probably the biggest similarity between the workflows that we each came up with the pieces that we did for Screen Knowledges, is using the glitches; knowing what sort of movements create a very specific result where there's still that unpredictability, but you are directing it.

Eron: Yeah, and the big moment was when I realized I could turn the camera around.

Kent: Yeah?

Eron: This was the move I never made when I was doing the experimental music photography. This was a huge realization. Now I have this technique which allows me to show the screen, the VFX, the time, the haziness of self. Much like you're breaking the surface of video games so you can see past the facade, these digital images were deconstructions of the fundamental fiction of flow: going into the magic window. Pointing out it's not a window. It's a panel that displays things based on outputs from hardware that you're sitting and manipulating in a room, with all this other crap going on! We're acknowledging the rest of the crap going on. The whole Screen Knowledges show is about different ways to get at that.

Kent: Yeah, it's like when you play with an Etch-a-Sketch, and you erase a very specific square of the screen so that you can peak at the mechanism underneath. So you make a little window for yourself to see the world underneath.

Eron: It was weirdly like learning to remember. I don't know if that makes sense? The whole process felt like a remembering: Remembering my body, remembering the computer. Remembering the hardware. Remembering the crap that's smeared on the screen, because that gets captured when you're doing this technique, because it'll glare weird.

Kent: Yeah, it's like when you catch yourself realizing your own sentience.

Eron: For me having this really severe anxiety and depression for multiple years, this process of photographing while playing became a way for me to remember to be alive, to not check out. The camera awkwardly dragged me back into remembering: “I’m here, I'm a person, my fuck-ups are okay. I’m this crappy person up playing Overwatch at 3 AM and I should really go to bed, but you know what? That's not the worst thing anyone could ever do in life. You're here. That's enough.” It became the way of being more present with what I was doing with games, rather than just using them to check out.

Kent: Pulling yourself back from the distraction just a little, just enough to check in on yourself.

Eron: Yeah. Somewhat comically in this case because the camera so much interrupts what you're trying to do in the video game. Just grab a pint glass and try to play Overwatch but never put the pint glass down. You really need three hands to do that!

Kent Sheely: So, taking the photos [for Valhalla Nocturnes], you found it difficult to actively play the game at the same time. That was actually part of the process that I was really interested in seeing. Was it simply the inclusion of the physical camera that caused the distraction? Or do you generally run into similar challenges trying to succeed at the game while also creating work from that?

Eron: Artistic disruption is a standard technique for me. I really very much love running interference in the materiality of making photographs. Much of my work has been about trying to actually get people to notice the things they don't normally notice. One of the first steps is always acknowledging the thing you're looking at for what it is. It's like remembering a painting's a painting. That's why I like Jackson Pollock so much. I mean, I know everyone kind of has a love-hate relationship with him—

Kent Sheely: Mixed feelings…

Eron: The one thing I love is that he used car paints and house paints. There's cigarette butts stuck in there. There are footprints. He's using the materials of his every day life in post-WWII suburban America, right? It makes you re-confront physicality. You're never going to pretend that one of his paintings is a beautiful landscape. And simultaneously you're also being confronted with a new physical arrangement of things you see around you all the time but never notice. So in Valhalla Nocturnes, the camera-as-disruption becomes the physical metaphor.

Kent Sheely: But at the same time it's kind of like the observer effect: when you observe and try to document it, it changes the thing that you're documenting.

Eron: Oh, and triply-so when you're talking screenshots. The moment you're starting to work in these video games, you’re disjuncting our preconceptions about the medium — Everyone always says, “Video games are gonna be the holodeck". But that seems so fundamentally to miss the point of why video games would be interesting to me. It seems to disregard some many things beyond “realism” for instance. I have very little interest in realism. It seems to disregard materiality, realism forgets these computers heat up on our laps.

Kent Sheely: Like for half an hour you can be Genji.

Eron: It's seductive to forget you exist. But it ultimately strikes me as artistically and socially destructive to disembody yourself. For me, the art is a way to assert my own being-ness, in all of its crappiness and incompleteness.

Kent Sheely: Right. You're turning the focus back on yourself. It's sort of like a lucid dream in a way. Like you were suddenly aware. The camera flips around and you're aware that you're a person in front of a screen.

Eron: Yeah, it's about retraining a degree of meta-critical conceptual control. Understanding that I am doing this thing [playing a video game] as a choice rather than just sliding under the digital river Lethe. Every time you're trying to slide in, the camera's like, “Nope, you can't do that. You can't headshot that. You can't strafe. You're dead because you’re trying to hold this camera.” It's kind of like a little like tap on the shoulder.

Kent Sheely: “Hey look in your right hand, you've got a mouse.”

Eron: And I’m no longer just existing to improve my aim accuracy on McCree from 38 % to 39 %. I also have this social obligation to make interesting things that I know have to go on a wall eventually.

Kent Sheely: Yeah, it's like a constant notification that something is happening outside.

Eron: Playing video games can be about fun, but what's even more interesting to me is having an experience in a video game I want to talk about with my friends. Having something so interesting happen that I want to talk about it is another tier above “enjoying” a video game. The camera becomes a way of reminding me over and over and over and over that you are a part of that social contract: “You're here to share something. So bring something interesting back with you. You might be diving, but bring something interesting back!”

Part 1 of this series can be found here.