Static Electricity: On Photography in Videogames

The following guest article by Lana Polansky - a Montreal-based game critic, crafter, writer and professional scowler - first appeared on her own blog. She was kind enough to allow me to republish this excellent and thoughtful article here as part of VGT's series on in-game photography, Screenshot Deluxe - be sure to check out Eron Rauch's great article on the topic as well as my essay here.

You can find more of Lana Polansky's work at sufficientlyhuman. com and follow her on Twitter. Thanks, Lana!

Killing Floor is one of the most unforgivably ugly games I have ever played. The FPS is about balls-to-the-wall grit and brutality. Best played as a co-op game, Killing Floor is not made for the patient sniper: enemy chokepoints are everywhere, writhing with ghouls and zombies, attacking you and your squad as mercilessly as the map architecture affronts the senses. Everything is overlayed with a grainy filter; set pieces are broken, abandoned and often aflame. Every nook and cranny screams violence, dereliction, and mortal peril.

I spend a great deal of my time in Killing Floor waiting for a server to open up, spectating—or dead and waiting for the level to end, as is far more often the case. I’m not really any good at it, to the dismay of strangers my friends and I sometimes team up with. But, really, it’s all the better for me. Waiting around gives me an opportunity to explore the spaces to their limits. missing textures and all. When not saddled with waves of ravenous monsters coming to the slaughter, I get to look around and see seams of humanity poking through these maps that want me to believe in death and destruction more than anything else. I look around and I see a broken skyline at the end of a world; light particles flickering across a darkened tunnel like falling snow; an abandoned computer desk in a musty biotics lab, papers strewn and chair overturned. I’m no photographer, but I line up a shot and hit F9 on my keyboard anyway.

Robert Overweg actually is a photographer. His series, “The End of the Virtual World,” explores visual bugs and glitches in videogames. He prefers more photorealistic games, like Left 4 Dead and Half-Life 2, which were “at the forefront of new technologies and development” when he was making his series, “and are part of our modern day pop culture.” He says they therefore ought to be “tampered with, reviewed and questioned.” His photographs depict such things as corridors with missing textures and NPCs hovering in the sky, hugging.

“More and more I am finding out that instead of playing the game—i.e. shooting each other—I seek silence, a place to get lost, a place to reflect, which is interesting because during boredom and nothingness come our best moments of reflection and inspiration. This nothingness is a big contradiction with the actual goals […] of the game,” Overweg revealed to me. This is complicated in games like Proteus, The Graveyard or Journey, where much of the action is based in things like reflection, meditation and exploration. But certainly, in games as we often know them—and absolutely in the case of Killing Floor—the silent introspection of photography is at odds with the mechanical focuses of the game. There isn’t a lot of time to stop and stare because the game would rather have us interact by doing.

Photographs pull things out of their original context and superimpose different layers of meaning onto them

Perhaps the reason Killing Floor feels so different when I’m playing is because the photographic context is in direct contradiction with more active, ludic ones. Photographs, if you listen to Susan Sontag or Roland Barthes, pull things out of their original context and superimpose different layers of meaning onto them: there’s the objective truth that the photo is freeze-framing, the way that truth is lit and framed and cropped by the photographer, and then there are the interpretations made by the observer about what the objects in the frame represent, both in a tangible and abstract sense. When I’m playing Killing Floor, dynamically moving through it, doing things within its confines, I’m more likely to experience the game as intended: as a dank, dark, carnal, hostile force. When I’m taken out of that context and am able to watch the game from a safe distance, some weird trick of programming allows the camera to move around in any direction, at any angle, through any object. I can see the world from perspectives that are totally limited to me when I’m playing. I’m able to exist outside the system and am more capable of making my own meaning out of the experience.

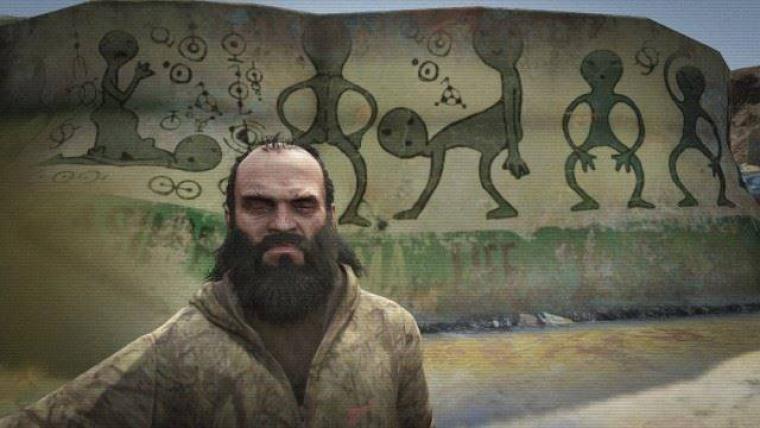

This takes on another layer of context as soon as I snap a screenshot. I’m looking for things that make the game feel warmer and more human. I’m specifically framing the photos I find to reveal a likely-unintended compassion from the map’s designers. Often, these are typical tropes found in post-apocalyptic fiction: cryptic graffiti bleeding from the walls and overturned cars, the odd dead scientist decomposing in a corner. You know, the usual. Sometimes I find things that are oddly beautiful: the aforementioned snowy lights and broken skylines, for instance, or an endless floor, or a distant sunset. I’m able to so decontextualize these snapshots from the harshness of their world that observers can’t believe it when I tell them which game they’re from.

I spoke to Ray Neilson, a friend and self-professed amateur photographer—as in, has had showings at “local cafes,” which is good enough for me—about the phenomenon of screen-shotting and photography of virtual spaces. He told me that one of his favourite games to take pictures in is Kerbal Space Program, the cute but startlingly accurate sandbox space-flight simulation. He takes photos of the planets he’s been to, of traveling space debris, of the shadow of his spacecraft against the light of some sun, because the in-game marker system is so impersonal. “The picture is more embodied than the flag in the map view,” he says. A little flag pin on a virtual map can’t capture a memory quite like a photograph can, especially in a procedurally-generated universe like KSP, where the likelihood of never seeing a specific configuration of objects again is plausible.

The conceptual and visible spaces of games influence how we behave, how we see ourselves as actors in the environment and how we see others

Neilson believes that games share the most in common with architecture. Mostly, he says, they’re about inhabiting designed space, enacting and observing movement according to the rules of that design. This design limitation is even more pronounced in game spaces than other kinds of spaces, since “traversing the space is different when you’re bound by the game rules—to differentiate it from spectator mode, etc.” Mode of traversal of space—and therefore mode of perspective—comes in handy when talking about games like Killing Floor.

There are certain things we accept when we enter into contract with game rules and limitations—we tend to refer to this contract as the “magic circle,” coined by historian Johan Huizinga. The conceptual and visible spaces of games influence how we behave, how we see ourselves as actors in the environment and how we see others as well. Any game will have us embodying certain roles (playing a Medic in Killing Floor will yield more supportive behaviour, whereas being a Sharpshooter is more about raking in headshots). Maybe that goes without saying, but I think it’s helpful to think of these performative elements as delimiting contexts in which to view the game. In other words, how I act while the game is being played, and therefore how I see the game, is highly dependent on the mode in which I’m traversing the game space and whether the pace (where I move and how quickly I move to it) and view (simply, the camera perspective) are in my control or not. When the photographic lens is in my control, then the space that I show myself, capture, and show to others, is destabilized and taken out of context from the intended experience.

Traversal of space needs another dimension: what kind of space is being traversed. In KSP, an ephemeral, procedural sandbox world is being photographed. The photographs Neilson takes become symbols of memory and permanence existing outside the game. They’re reminders that Neilson was there, and that “there” existed in one form or another. This kind of game photography can be seen as a kind of nature photography, bringing a human touch to the random-feeling elements of floating rock through space. It’s not totally unlike snapping photos of a meteor shower, both to capture something fleeting and sublime—divine, even—but also to put a personalized imprint and emotional perspective on an otherwise uncaring cosmos.

For Overweg, capturing glitches in worlds that attempt to be picture-perfect facsimiles of reality is a way to expose the fact that, after all, games are inevitably engraved by their makers: “Games are still created by humans. When they forget something due to a human error glitches can appear, thus glitches are the most human aspect of gaming. Also I love it when something gets damaged but becomes more beautiful.” Traversing a “realistically” stylized game like Left 4 Dead in an active player context often means seeing glitches and bugs as amusing or annoying mistakes rather than indicators of humanity. Pulling glitches out of that context and portraying them as frozen moments in time allows us to reflect, to see them in a new light. Overweg remarks that games, like many other art forms, demonstrate the limits of our imaginations because our tendency is to reproduce “what we already know.” He even notes that although he can take a photo in-game from any perspective he likes, the ones that are the most resonant and popular are the ones taken from angles that people find most familiar. It’s makes the thing—no matter how unnatural it is—feel more present, attainable, real. Still, Overweg believes in looking beyond the game as it is meant to be played and seen. “My first series of photographs where I make the exact same photos as in the physical world, it took me a while to see this and break free from it. Sherry Levine once said, ‘Any photographer who goes out to photograph goes out with preconceptions of what can be found.’”

I find myself engaging in a similar dialogue when I spectate in Killing Floor. I’m not necessarily looking for glitches or have an explicit desire to make placement markers, but I am looking for signs of life among the crusty, grainy, zombified maps of the FPS. I’m looking for little touches of someone telling a story with well-placed objects, or the incidental beauty of seams in skyboxes. Much like for Overweg and his glitches, these little quirks and errors in Killing Floor betray a human hand guiding their design. This is especially intriguing for me because Killing Floor’s map design is so scattershot. There are the official maps designed by Tripwire, there are the mod maps made by players and shared across the Stream network, and then there are the maps made by fans for contests, or just happened to impress the developers so much that they included them as part of the “official” map roster. It means there’s no one artistic voice or style, that the maps are all kind of a hodge-podge of varying quality, requiring different sorts of tactics and evoking slightly different variants of “creepy” depending on who made them. Some are grittier than others. Some are goofier than others. Some are sadder than others.

Like any space, humans not only feel a need to occupy games, but leave and document marks of having touched them

I think the common motifs throughout Neilson’s, Overweg’s and my own endeavours in in-game photography are embodiment, perspective and permanence. Many games can feel impermanent, and the way we embody them and see them can be constrained and tightly controlled. Memories too fade and are fluid. But like any space, humans not only feel a need to occupy games, but leave and document marks of having touched them—this actually might explain some of the lasting endearment toward Pokémon Snap, a “rail shooter” where taking snapshots of Pokémon in their natural habitat, so to speak, brought us nearer to them. We crave immortality—we hate to think that our efforts in a game revert to code and can be washed away like a sandcastle at high tide. We like to crystalize objects outside of ourselves that confirm not only what we saw, but how we felt when we saw them.

Yannick Lejacq, musing on the phenomenon of players taking “selfies” of their avatars in games, wrote,

“For all the ink that’s been spilt about selfies this year, it’s really not that hard to explain why people like to take them. Whether they serve an archival or purely social purpose, photographs has always helped us document and make sense of our lives. Taking pictures of yourself in a videogame, however, poses another question altogether. If the ‘selfie’ truly instrumentalized our inherent narcissism, videogames would seem like an odd vehicle for doing so. The connection to one’s self in a game is already tenuous. You might be controlling this particular Trevor (or Franklin, or Michael) in GTA V, but he looks an awful lot like the other 30-million-plus Trevors that are out there jacking cars and killing people.

Maybe that’s the point. One night shortly after GTA V was first released, my friend Jake called me up to say he was in my neighborhood and not-so-subtly invited himself over to try the game out. I’d been tearing through the game in an attempt to review it, and actually having another human being sitting next to me while playing it was unexpectedly comforting.

‘You need to have someone else here,’ Jake said when I pointed this out to him. ‘To see all the crazy shit that’s happening.’”

Selfies, both taken in real life and in games, are a way for us to insert idealized versions of ourselves into the space

If having a friend there to see you play is outside confirmation of all that crazy shit, then posting a selfie on social media for the world to see is a downright attempt at photojournalism. But I think there’s something else here. Selfies are a way of asserting oneself in a space, both in terms of the photograph but also within a setting often contrived by the photographer. One of the concepts videogame marketing has tried to sell us is this idea of immersion: of embodying a videogame character and space so much that you suspend disbelief enough to believe you’re really there. Part of the justification for greater photorealism in games is this ambition to totally immerse, but this is somewhat absurd and has been torn to pieces by various critics and/or designers.

Instead, I think players embody their characters not by “becoming” a hero or a space marine or whatever. I think that concept is fundamentally backwards. Instead, I think players make their avatars (who are usually empty archetypes anyway) become them, and the game selfie is part of that. Selfies, both taken in real life and in games, are a way for us to insert idealized versions of ourselves into the space. We etch our personalities onto games by anthropomorphising, posing and framing our avatars. We give them motivations for doing things that are actually our own motivations. Many of us colonize spaces with our personalities, interests and desires—and when a game sets limitations, we find ways to bend, subvert or break them in order to superimpose ourselves onto them. Like photographing glitches in Left 4 Dead, planets in KSP, or authorial idiosyncrasies in Killing Floor, taking in-game selfies is a way to decontextualize the space by isolating it and injecting oneself into it from a desired perspective.

Game photography is, often, a reflection of the human impulse to leave artefacts of ourselves wherever we go, to leave little bits of ourselves behind as affirmation that we definitely existed, and that we made an impact. The Abandoned Pics Twitter account elicits widespread fascination because it documents human structures left behind—not torn down, just left—decrepit or retaken by nature. I see a lot of my own fascination with those photos as reminiscent of my interest in documenting “human” artefacts in Killing Floor. I get a thrill from strewn objects that serve no other purpose than to declare that life was once there. Maybe game selfies can be compared to another Twitter account, Faces in Things, that posts pictures of inanimate objects bearing the illusions of human or animal faces. It reminds me of Overweg’s claim that we seek the familiar no matter where we go, for comfort and for reassurance. We see ourselves in things that aren’t about us—that are totally indifferent to us—in all kinds of spaces.

Virtual spaces, especially, can seem so fleeting, and our traversals through them so disembodied. To take a photograph is to embody a space, to make it feel like a place that was once visited, to cement the fact that the things we thought and the feelings we felt had meaning. Games photography, if nothing else, “should or could inspire to take a moment of contemplation beyond games into the web and physical world,” says Overweg. Game spaces are so dependent on things like movement and temporality, but a photograph takes them out of time, makes them static keepsakes of a point of view that can exist outside the reality of the game, a meditation on timelessness and a grab at immortality.